History of Fort Union Trading Post

The Grandest Fort on the Upper Missouri River

Photo Credit: Fort Union Trading Post National Historic Site, Public domain, via National Park Service.

History of Fort Union

Trading Post

The Grandest Fort on the Upper

Missouri River

Photo Credit: Fort Union Trading Post National Historic Site, Public domain, via National Park Service.

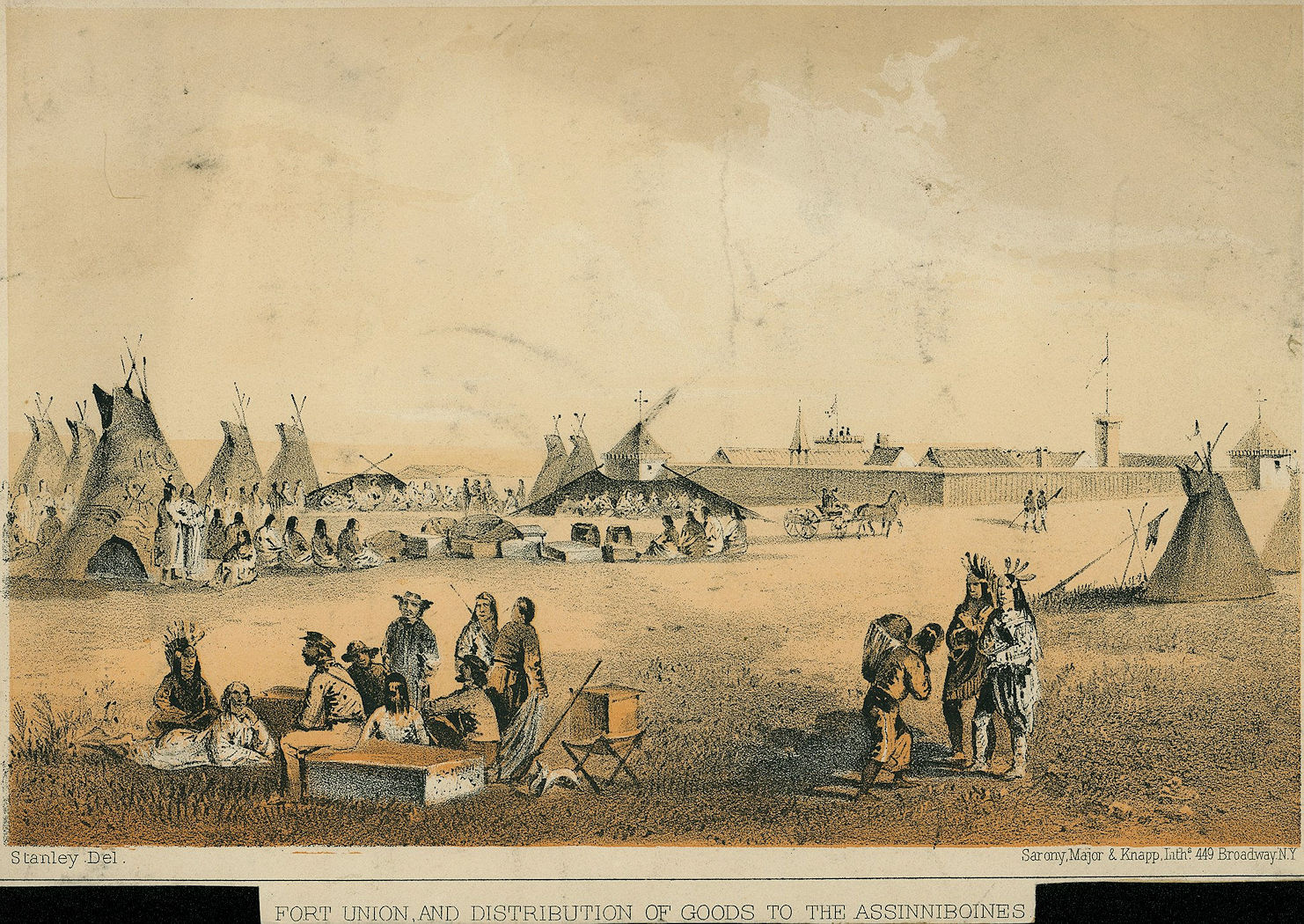

In 1828 the Assiniboine Indians requested that John Jacob Astor’s American Fur Company establish a trading post in their homeland to protect them from hostile tribes. Kenneth McKenzie thus founded Fort Union in what is now North Dakota. Strategically located near the homelands of 10 Northern Plains tribes[1], Fort Union, possibly first known as Fort Henry or Fort Floyd, was built in 1828 or 1829 by the Upper Missouri Outfit managed by Kenneth McKenzie and was capitalized by John Jacob Astor’s American Fur Company.[2] Until 1867, Fort Union was the central, and busiest, trading post on the upper Missouri, instrumental in developing the fur trade in Montana. Here Assiniboine, Crow, Cree, Ojibwe, Blackfoot, Hidatsa, Lakota, and other tribes traded buffalo robes and furs for trade goods including beads,[3] clay pipes,[4] guns, blankets, knives, cookware, cloth, and alcohol. Historic visitors to the fort included John James Audubon, Sha-có-pay, Captain Joseph LaBarge, Kenneth McKenzie,[5] Father Pierre-Jean De Smet, George Catlin,[6] Sitting Bull, Karl Bodmer, Hugh Glass, and Jim Bridger.

At first, Indians traded beaver pelts for Euro-American goods because of the popularity of beaver hats in the East and in Europe. When silk and woolen hats became more popular during the 1830s, demand for beaver pelts decreased, and the trade shifted to bison robes.[7]

During the historical period, Fort Union served as a haven for many frontier people and contributed to further economic growth on the American frontier. As headquarters for the American Fur Company, it played a primary role in the growth of the fur trade and allowed fur trade entrepreneurs to exert considerable influence in forming policies that affected the Indian nations of the region. The presence of the fort near the northern border of the United States also symbolized national sovereignty in the region.[8]

Video Courtesy of the National Park Service

The fort maintained a large inventory of firearms that were traded with Indian tribes for furs. In turn, Indians used the firearms in hunting for furs and buffalo robes. Northern Plains Indians preferred the English-made “North West Gun,” a smooth-bore flintlock, because of its reputation for quality and reliability.[9]

Conflicts between Euro-American traders and Indians were less frequent around Fort Union than conflicts between the Indian tribes themselves.[10] However, during the summer of 1863, when many tribes along the Missouri River became openly hostile to whites, Fort Union was nearly under siege, and steamboats and their passengers were exposed to significant danger.[11]

Fort Union was the most important trading post of the Upper Missouri fur trade until smallpox decimated the population of numerous Plains tribes. After resentment toward the white encroachment into Indian Territory led to Sioux hostilities, the need for trading posts declined as the call for military posts increased. The Army dismantled the post in 1867 to build Fort Buford, but historic accounts provide information about the Upper Missouri fur trade and the American Indians who exchanged goods at the Fort Union Trading Post, which is now Fort Union Trading Post National Historic Site.

Established near the junction of the Missouri and Yellowstone rivers, Fort Union Trading Post was a 220 by 240 foot quadrangle enclosed by vertical logs with bastions at the northeast and southwest corners. Fort Union had two points of entry, but the gate on the south side facing the river was the main entrance for the trading public and wagons. Once inside the complex, traders and notable visitors found several prominent buildings surrounding a central courtyard where the flagstaff stood. On the west side of the gate, a long building served as the staff sleeping quarters, and on the east, a similar building housed the retail store and stockroom.

Across from the main gate stood the striking bourgeois house, where McKenzie and his successors lived. The largest of the Fort Union buildings, this two-story structure had glass windows, a fireplace, and other modern conveniences. Behind the bourgeois house was the Fort Union kitchen, which was also near the trading post’s bell tower. The fort also had an icehouse, a stable, a cut stone powder magazine, and blacksmith shops. White leather tents or tipis surrounded the flagstaff, and a reception room by the main gate was where the Indians traded their goods.

Although the American Fur Company built Fort Union at the request of the Assiniboin Indians, the company also welcomed many of the other Upper Missouri tribes into the post’s reception room. Other than the Assiniboin, the most common Northern Plains tribes trading at Fort Union were the Crow Indians who lived on the upper Yellowstone River, and the Blackfeet who claimed lands on both sides of the border between the United States and Canada. Also welcomed at Fort Union were the Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara who lived along the Missouri River; the Dakota Sioux; the Plains Cree from eastern Canada; and their allies, the Ojibwa, from the Great Lakes region.

The peaceful Northern Plains tribes traded their renowned buffalo robes, which were becoming a highly sought after commodity at the time of Fort Union’s establishment. By the 1830s, the demand for beaver pelts began to decline, as silk hats were preferred over beaver hats, and the demand for tanned buffalo robes increased. Fort Union thrived because of the post’s proximity to the Plains Indians. In exchange for the Plains tribes’ buffalo robes, the Americans traded axes, firearms, and other technological goods. Fort Union also installed a distillery in 1832 to produce corn whiskey to offer the Indians in exchange for their buffalo robes.

Although trading liquor proved successful, the establishment of the distillery nearly resulted in the loss of the American Fur Company’s license. It was unlawful to bring liquor into Indian Territory because it gave Fort Union a competitive advantage over other fur companies, and in 1833 the government ordered the American Fur Company to destroy the distillery. Eventually, given their tarnished reputation, the incident forced John Jacob Astor and Kenneth McKenzie into early retirement, and by 1834, Fort Union was under new management.

Following McKenzie’s departure, Fort Union welcomed several outstanding managers (called “bourgeois”), including Alexander Culbertson, Edward Denig, James Kipp, and Charles Larpenteur. As the bourgeois, these men managed the post and were responsible for employing workers and establishing successful trading relationships with the tribes. Assisting the bourgeois were the clerks, who helped maintain the fort’s inventory of traded goods and kept track of tools, equipment, animals, and food. Other employees at Fort Union worked as interpreters, hunters, herders, traders, blacksmiths, carpenters, and masons. Together, these workers, the bourgeois, and their families made up the 200 residents needed for the successful operation of the trading post.

Although most of the residents at Fort Union were employees of the American Fur Company, the trading post had some notable visitors. Among them were George Catlin, Prince Maximilian of Wied, Father Pierre De Smet, John James Audubon, Karl Bodmer, and Rudolph Frederich Kurz, whose paintings and written accounts of life at the post provided the basis for the National Park Service’s reconstruction of the site.

At Fort Union Trading Post National Historic Site, visitors can explore the reconstructed portions of Fort Union including the walls, stone bastion, Indian trade house, and Bourgeois House. The visitor center and bookstore are at the Bourgeois House. Living history programs are available during the summer at the Trade House. Visitors can also walk the Bodmer Overlook Trail to the location where Karl Bodmer once stood and painted “The Assiniboin at Fort Union” in 1833. Each year the site hosts a living history trade fair, but schedules and dates vary. For more information on the annual Fort Union Rendezvous, visit the Fort Union Trading Post National Historic Site.

Location & Contact

Address: 15550 Highway 1804, Williston, ND 58801

Email & Phone: [email protected] | 701.572.9083

Website

Fort Union Trading Post Gallery

Resources

Crazy Crow Articles

Current Crow Calls Sale

January – February

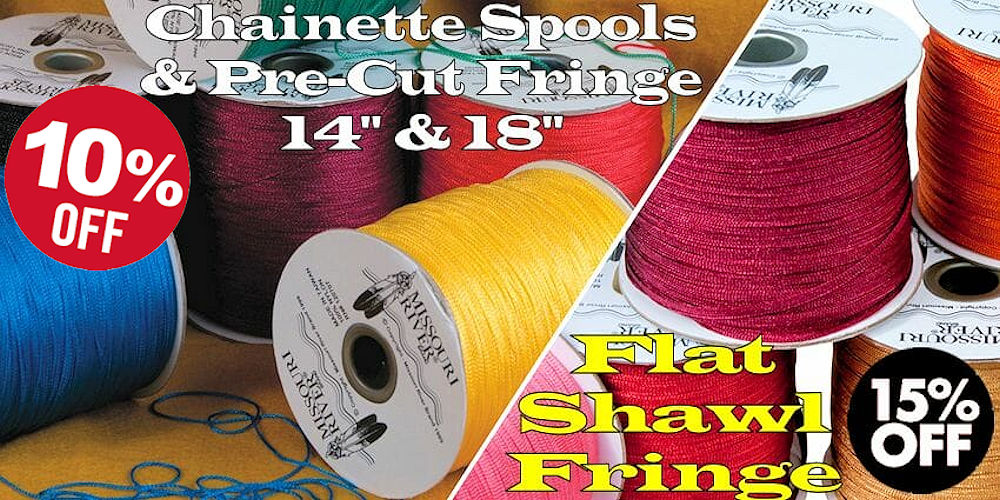

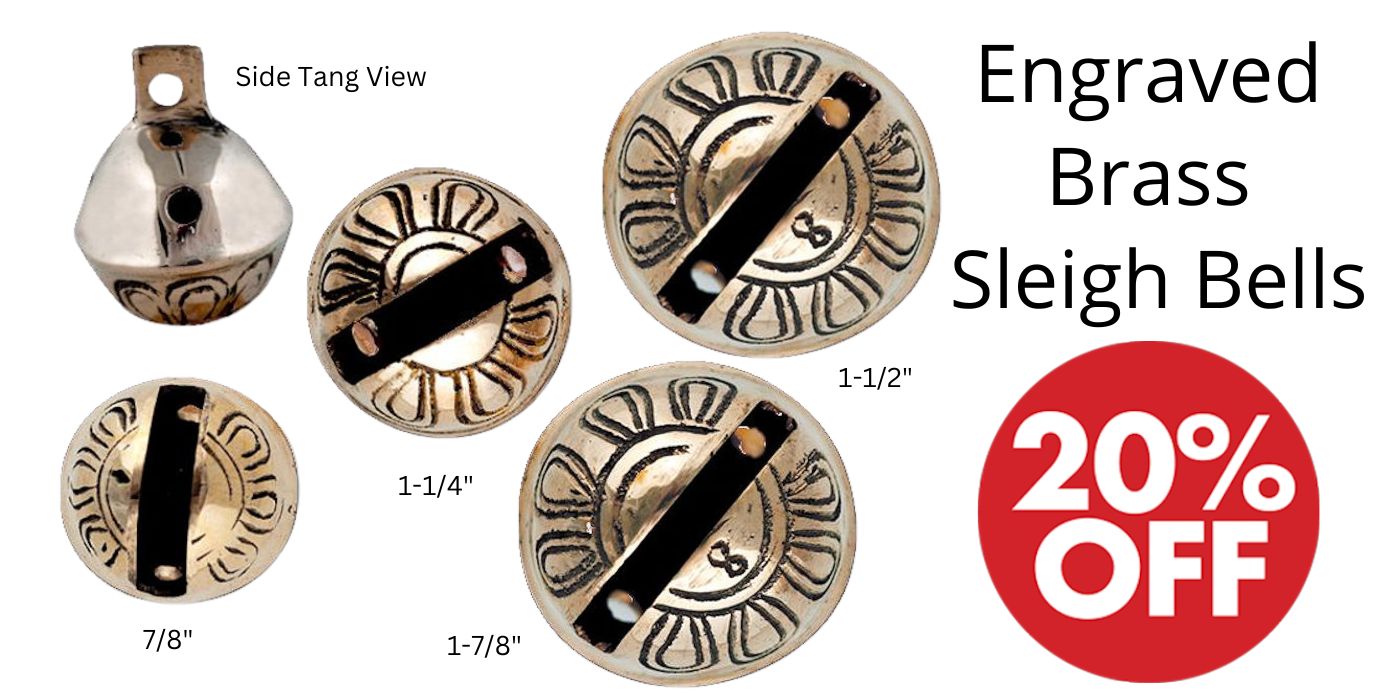

SAVE 10%-25% on popular powwow, rendezvous, historic reenactor, bead & leather crafter supplies. Crazy Crow is starting out the New Year with savings on many popular craft supply items like Plains Hard Sole Moccasin Kits, Chainette Spool and Pre-Cut 14 & 18 inch Fringe, Flat Spool Fringe, as well as big savings on very popular items like most types of our brass beads, artificial sinew, bone hair pipes, Peyote Kettles and Drum Covers, select hand-made Frontier Knives, and engraved brass sleigh bells. Of course you can order everything online 24×7.