Fur Trade Gift Diplomacy in the Pays d’en Haut

Great Lakes Area 16th-19th Centuries

The North American Fur Trade: Timeline, Transitions, and Tribal Impacts

Note: This article is still being added to, particularly with samples of the types of trade silver, peace medals, and gorgets.

By Crazy Crow Trading Post ~ Updated February 12, 2026

Fur Trade Gift Diplomacy in the Pays d’en Haut Great Lakes Area 16th-19th Centuries

Symbols, Alliances, and the Evolution of Fur Trade Relations from the Late 1500s to the Mid-19th Century

Note: This article is still being added to, particularly with samples of the types of trade silver, peace medals, and gorgets.

By Crazy Crow Trading Post ~ February 12, 2026

In the vast and contested landscapes of North America, particularly the Pays d’en Haut—the “upper country” (the “upper country” encompassing the Great Lakes region, including parts of modern-day Michigan, Wisconsin, Minnesota, Ontario, and Quebec)—gift diplomacy was the lifeblood of the fur trade. This practice was not merely an exchange of material goods but a profound cultural and political mechanism for forging alliances, maintaining peace, and ensuring the flow of furs that drove colonial economies. From the earliest encounters in the late 1500s, when French explorers first navigated the St. Lawrence River and encountered Algonquian-speaking peoples and the Iroquois Confederacy, to the mid-19th century as the trade pushed westward into the Rockies and Pacific Northwest, gifts served as tangible symbols of reciprocity and obligation.

For those deeply familiar with the era, such as scholars versed in Richard White’s concept of the “middle ground”—a negotiated space where neither Europeans nor Indigenous peoples held absolute power—gift diplomacy highlights the fragility of alliances built on mutual dependence. Indigenous leaders, lacking coercive (ability to force) authority over their kin and warriors, relied on redistributed gifts to sustain influence and consensus. Europeans, in turn, used these exchanges to secure loyalty, military intelligence, and access to pelts amid fierce competition. For newcomers to this history, think of it as a system of mutual promises sealed with objects: a silver pendant or peace medal given by a colonial “Great Father” elevated a chief’s status, allowing him to rally support, while the giver gained a strategic partner in a dangerous frontier.

This diplomacy evolved through French, British, and American phases, adapting to wars, treaties, and economic shifts. It incorporated a wide array of items—from small metal and horn containers for everyday utility to ornate trade silver pendants symbolizing spiritual and economic ties, and formal peace medals affirming treaties. As the fur trade expanded from the Great Lakes to the Missouri River basin, Ohio Valley, and beyond, these gifts reflected broader changes: the decline of mercantilist monopolies, the rise of free-market American enterprises, and the tragic erosion of Indigenous autonomy.

[Background on Mercantilism:] An early form of capitalism where European powers granted sovereign charters to companies (e.g., Hudson’s Bay Company) for monopolies over trade regions, products like furs, or both, fostering zero-sum competition to enrich the crown through colonial extraction and restricted markets. Post-Revolutionary America bypassed these constraints, enabling free-market firms like Astor’s American Fur Company to achieve 20-40% cost/price advantages by avoiding bureaucratic layers, exclusive ports, and specie bans, accelerating the shift to modern capitalism amid the fur trade’s westward expansion.

Drawing on historical inventories, museum artifacts, and archaeological finds, this exploration details how these objects functioned in diplomacy, their materials and designs, and their enduring significance for historical reenactors portraying Voyageur rendezvous (late 16th to early 19th centuries) or Mountain Man gatherings (1825–1840), where alliances and trade were reenacted amid period camps, black powder demonstrations, and cultural exchanges.

The French Era: Onontio and the Foundations of Reciprocity (Late 1500s–1763).

The roots of gift diplomacy trace to the late 1500s, when French fishermen and explorers began trading metal goods for furs along the Atlantic coast and St. Lawrence. By the early 1600s, Samuel de Champlain’s alliances with the Huron and Algonquian groups formalized the practice. Gifts were essential in a world where Indigenous societies operated on kinship and consensus; chiefs redistributed items to warriors, binding them through obligation rather than command. The French governor, dubbed Onontio (“Great Mountain” or “Great Father”), hosted annual councils at Montreal or Quebec, distributing goods to affirm paternal protection.

Small containers were ubiquitous gifts, prized for their practicality in a mobile frontier life. Tobacco boxes, often oval or rectangular with hinged lids, stored snuff or tobacco but were repurposed for percussion caps, nipples, or small gun parts in later muzzleloading eras.

Snuff boxes, more ornate, appealed to personal tastes, while pill boxes—round or oval—held medicines, powders, or spices. Horn containers, crafted from cow or buffalo horn with wooden or metal plugs, were lightweight and moisture-resistant, ideal for priming powder or salt. Materials like brass (durable and corrosion-resistant), German silver (bright and affordable), tinplate (inexpensive), and copper were favored, primarily imported from Britain, France, or Germany. These European-manufactured items, sourced by companies like the Compagnie des Habitants, underscored the trade’s global networks.

Pendants in pewter, silver, or copper—shaped as turtles, beavers, kissing otters, or Lorraine Crosses—carried deeper symbolism. Popular from the late 17th to early 19th centuries, these 2–3-inch ornaments were produced by silversmiths in Montreal, Quebec, Philadelphia, or Detroit. Silver was most prestigious for its luster and value, pewter (a tin-based alloy with copper and antimony for strength) offered a silvery appearance at lower cost, and copper provided simplicity. Turtles evoked Indigenous creation stories of “Turtle Island,” symbolizing earth and endurance. Beavers represented the fur trade’s core commodity, embodying industriousness and community. Kissing otters signified love, unity, and companionship, reflecting prized otter pelts. Lorraine Crosses, introduced by French missionaries, blended Christian heraldry with Native reinterpretations as dragonflies or spiritual messengers. Produced by silversmiths in Montreal or Quebec (e.g., Robert Cruickshank), these pendants were most popular from 1680–1820.

Pendants such as these were tailored to regional preferences: crosses resonated with Iroquoian groups influenced by Jesuits, while animal motifs suited Algonquian tribes in the Pays d’en Haut. Natives wore them as adornments on clothing, bandoliers, or necklaces, signaling status and alliances. Europeans, including coureurs de bois (independent French traders) and voyageurs (canoe-based transporters), adopted them to blend cultures and build trust. Alcohol (brandy or rum) and firearms (smoothbore muskets) were potent but controversial gifts; French policy permitted them to secure military aid against the Iroquois, but shortages or exploitative use strained relations, as seen in the Beaver Wars (1609–1701).

Click to enlarge image.

Nikki Rajala’s Voyageur Blog

Background on Alcohol and Firearms in Fur Trade Diplomacy: Alcohol (brandy or rum) and firearms (smoothbore muskets) were potent but controversial gifts, with policies fluctuating on-again off-again due to ethical concerns over exploitation versus competitive necessities; French, British, and American traders often expressed reluctance—citing alcohol’s role in fostering dependency, social disruption, and violence among Indigenous communities, as well as firearms’ potential to escalate intertribal wars or turn against colonists—but supplied them anyway to secure alliances, outcompete rivals, and meet Native demands for these inelastic goods that enhanced hunting, warfare, and status. Shortages strained relations, as during the Beaver Wars (1609–1701), when Iroquois access to Dutch and English guns shifted power balances, leading to devastating conflicts; exploitative use, such as trading diluted rum or withholding ammunition to manipulate terms, further eroded trust. Only smoothbore muskets—lighter, cheaper trade guns less accurate than rifles and prone to fouling but reliable for bulk production and field use—were predominantly traded, as they sufficed for Native needs without conferring the superior long-range precision of rifled barrels that emerged in the mid-18th century; traders deliberately avoided distributing advanced rifles, fearing they could equip Indigenous forces too effectively in potential combat against Europeans, thus preserving a technological edge amid the fragile middle ground alliances.

Background on Failures in Gift Diplomacy

Example of French Failures

When European powers deviated from the reciprocal practices of the middle ground—treating Indigenous peoples as subordinates rather than partners—the consequences were often catastrophic, disrupting alliances and igniting violence while the balance of power remained precarious. A key example occurred in 1753, when Pierre-Paul Marin de la Malgue (Sieur de Marin), leading a French expedition southward toward the Ohio River amid escalating tensions with the British, embodied the rigid European attitudes that clashed with frontier realities. Though Canadian-born, Marin’s approach reflected the preconceptions of officers influenced by European doctrines (as White notes, “officers fresh from France who did not understand the compromises and rituals of the middle ground”), imposing force to secure Native allegiance without sufficient mediation or consent. Commanding a significant army (specific size not detailed, but involving troops for building forts like Presque Isle, Le Boeuf, and Venango, likely under 1,000 in the core force given logistical constraints), the expedition aimed to establish French presence but was thwarted not by Native resistance but by the environment itself: drought-lowered rivers necessitated long, exhausting portages; troops cut wagon roads through dense terrain, leading to fatigue; scurvy and other diseases broke out amid poor supplies. White details the toll: “disease and exhaustion claimed the lives of four hundred of his men.” Marin himself died that fall in the forests, succumbing to illness. The survivors retreated, reserving small garrisons at new posts, dispatching a minor detachment onward, and sending the sick and worn-out home—abandoning broader objectives. This failure, as analyzed in Richard White’s The Middle Ground (particularly in discussions of 1750s imperial overreach), stemmed from prioritizing coercive force over alliance-building, alienating potential Native partners who were essential for supply and defense; it prompted reflections on the limits of power, with White emphasizing that “force had secured renewed allegiance on the Ohio, but that force could only be effectively deployed with Indian consent,” forcing a partial reversion to accommodative diplomacy to restore balance.

Example of British Failures

An even more severe breakdown followed the British victory in the Seven Years’ War (1756–1763), when General Jeffery Amherst—infamously associated with proposals to distribute smallpox-infected blankets—implemented austerity measures, slashing gift distributions and reframing Natives as conquered dependents rather than allies. This violated the expected reciprocity of the middle ground, eroding Indigenous leaders’ influence and sparking Pontiac’s War (1763–1766), a widespread uprising led by Ottawa chief Pontiac and involving multiple tribes across the Great Lakes and Ohio Valley. The conflict resulted in thousands of deaths, the capture or destruction of most British forts west of the Appalachians, and brutal frontier warfare; only after heavy losses did the British reinstate gifts and negotiations, learning the hard way that stability required adherence to diplomatic norms.

Example of American Failures

The pattern repeated during the American transition after the Revolutionary War (1783), as the U.S. sought control of the Ohio Territory amid British retention of forts (until the 1796 Jay Treaty) and ongoing Native resistance. Ignoring gift diplomacy, American commanders like Brigadier General Josiah Harmar (1790) and Major General Arthur St. Clair (1791) launched expeditions with inadequate alliances, viewing tribes as obstacles. Harmar’s campaign ended in defeat with 183 killed; worse, St. Clair’s force of about 1,400 suffered over 900 casualties (including 632 killed) at the Battle of the Wabash—America’s worst military loss to Native forces, surpassing Little Bighorn (1876, 268 killed). These disasters in the Northwest Indian War (1785–1795) stemmed from failures to engage in reciprocal diplomacy, fueling Indigenous coalitions under leaders like Miami chief Little Turtle and Shawnee chief Blue Jacket; only after General Anthony Wayne’s victory at Fallen Timbers (1794) and the Treaty of Greenville (1795) did the U.S. begin incorporating more diplomatic gifts to stabilize relations.]

The British Era: Crisis, Adaptation, and Mercantilist Competition (1763–1783)

Britain’s victory in the Seven Years’ War transferred the Pays d’en Haut, but cultural misunderstandings disrupted diplomacy (as mentioned above in ‘Background on Failures in Gift Diplomacy’. General Jeffery Amherst’s 1760 policy to halt gifts—framing Natives as conquered dependents—violated reciprocity, sparking Pontiac’s War (1763–1766). Warriors, deprived of expected goods, overran British forts, killing thousands and forcing a policy reversal. Gifts resumed as essential for stability, distributed at treaties like the 1768 Fort Stanwix accord.

Trade silver expanded: gorgets, crescent-shaped metal badges (3–4 inches wide), evolved from European armor remnants to Native status symbols. Originally shell or copper in Indigenous traditions, they were replaced by metal versions engraved with royal arms or cyphers. Pendants continued as diplomatic currency, worn by leaders to display bonds with the British Crown.

Click to enlarge image. Event & Photo Credit:

Des Plaines Valley Rendezvous

“A River Runs Through It”

Company badges and tokens emerged amid competition. The North West Company (NWC), formed in 1779, issued 1820 copper or brass tokens valued at “One Made Beaver”—a standardized unit for pelts. Struck in Birmingham, England, these coin-sized items functioned as scrip: trappers received them for furs and redeemed them for goods. Many were holed for necklaces, transforming accounting tools into ornaments among Natives and traders, bridging utility and symbolism. It should be noted that these badges were not intended as trade items, but for use by these ‘companies’; they are mentioned here to anchor them at this time in the fur trade era in this expanded Great Lakes area.

British mercantilism hampered efficiency: charters like the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) or NWC’s ties to the East India Company imposed monopolies, restricting ports (e.g., Canton for China trade) and inflating costs by 20–40%. Alcohol and firearms flowed, but ethical breaches eroded trust. Military badges, like those of Scottish regiments or Rogers’ Rangers (1755 light infantry in the French and Indian War), were identity markers rather than gifts, though they overlapped with fur trade regions.

The American Era: Factories, Free Markets, and Westward Expansion (1783–Mid-19th Century)

Post-Revolutionary War, Americans navigated British-held forts until the 1796 Jay Treaty. The U.S. Factory System (1795–1822), a government non-profit initiative, offered cloth, tools, blankets, beads, and limited alcohol/firearms at posts like Arkansas Post, aiming to build goodwill and undercut British influence. Criticized for inefficiencies by private traders like John Jacob Astor, it was abolished amid lobbying by his American Fur Company (AFC).

Astor’s AFC (1808) exploited free-market advantages: unbound by charters, it cut costs, carried diverse cargoes (including specie), and traded flexibly. Gifts included metal arrowheads (iron for sharpness and durability, triangular/barbed designs from 1750–1850s) and brass thimbles (for sewing moccasins or decorating bandoliers with beads and dew claws). Iron arrowheads, forged from scraps like gun parts, outlasted brass or copper, becoming most valuable in archaeology post-contact.

Peace medals formalized diplomacy: U.S. versions, starting with George Washington (bronze or silver, presidential portraits), were distributed at treaties to affirm “peace and friendship.” Thomas Jefferson medals, 2.5 inches in diameter, commemorated alliances during the Lewis and Clark expedition. Astor’s 1832–1833 silver medals (66mm), with his profile and crossed tomahawk-calumet reverse, were given at Fort Union to Plains leaders, blending company branding with treaty symbolism. Worn on cords, they credentialed chiefs, visible proofs of U.S. ties.

As the trade shifted west—via Missouri River forts and Rocky Mountain rendezvous—diplomacy adapted. Voyageur gatherings (up to 1810) involved French-Canadian canoemen exchanging furs at Great Lakes junctions, while Mountain Man events (1825–1840) featured resupplies amid primitive camps. Gifts sustained alliances with tribes like the Cree, Ojibwe, and later Sioux, but declining beaver by 1840 marked the era’s end.

Free-Trade Advantages for American fur trade companies, e.g., American Fur Company (AFC)

Astor’s American Fur Company (AFC, established in 1808) capitalized on the advantages of operating in a free-market environment: free from restrictive royal charters, it reduced operational costs, transported a wide variety of cargoes—including specie (hard currency in the form of gold or silver coins)—and conducted trade with greater flexibility. This diversity in shipments allowed Astor to maximize profits by carrying high-value goods like opium, ginseng, and manufactured items outbound to China, where beaver pelts fetched premium prices for hat-making, while returning with lucrative imports such as teas, silks, and porcelains; unlike charter-bound mercantile companies (e.g., the Hudson’s Bay Company, constrained by monopolistic rules and exclusive ports) or even private Canadian firms like the North West Company—which had to navigate through the East India Company’s charter monopoly for access to Canton, facing specie bans, limited trading options, and added fees that eroded margins—Astor’s unrestricted approach enabled multiple revenue streams, often yielding profits on every leg of the voyage and giving the AFC a decisive edge in the competitive global fur market.

The U.S. Factory System: Purpose, Failure, and Echoes of Mercantilism

The U.S. Factory System, operational from 1795 to 1822, was a government-initiated network of trading posts (known as “factories”) designed to facilitate fair and regulated commerce with Native American tribes. Championed by President George Washington and authorized by Congress under the Trade and Intercourse Acts, its primary purpose was to foster goodwill, build alliances, and counteract lingering British influence in the western territories by providing essential goods—such as cloth, tools, blankets, beads, and limited foodstuffs—at cost, without profit motives.

This non-exploitative approach aimed to protect Indigenous peoples from unscrupulous private traders, promote peaceful relations, and integrate Native economies into the young republic’s framework, while also gathering intelligence on frontier dynamics. Factories like those at Arkansas Post (1805–1810) and Sulphur Fork (1818–1822) served as outposts where federal agents exchanged U.S.-manufactured items for furs, emphasizing diplomacy over cutthroat competition.

Despite these ideals, the system failed due to inherent inefficiencies and external pressures. Government bureaucracy led to slow supply chains, inconsistent stock (often lacking high-demand items like alcohol and firearms, which private traders freely offered), and poor adaptation to Native preferences.

This made these “factories” uncompetitive against agile rivals like the Hudson’s Bay Company or John Jacob Astor’s emerging American Fur Company. Critics, including Astor, lobbied Congress, arguing the system stifled free enterprise and failed to secure economic dominance. By 1822, amid reports of corruption and financial losses (totaling over $300,000 in deficits), Congress abolished it, paving the way for private monopolies that accelerated westward expansion but often at greater Native expense.

In structure and intent, the Factory System represented a vestige of European mercantilism—state-directed trade aimed at national interests through monopolistic control—compounded by direct government ownership rather than chartered private entities (e.g., like Britain’s Hudson’s Bay Company). This “public mercantilism” prioritized geopolitical goals over market efficiency, mirroring Old World models where sovereigns granted exclusive rights to extract colonial wealth, but it clashed with America’s post-Revolutionary shift toward free-market capitalism, ultimately highlighting the tensions between regulated diplomacy and unregulated profit in the fur trade era.

Legacy: From Diplomacy to Reenactment

Gift diplomacy shaped North America’s map, economies, and cultures, though it often facilitated dispossession. Today, historical reenactors at Voyageur or Mountain Man rendezvous event revive this through period attire, black powder demos, and trade between attendees (of course this trade is tempered with credit card purchases at nearby trader booths), honoring the alliances that defined the frontier and the fur trade era that ushered in the expansion of America westward.

Rendezvous & Historic Reenactment Articles

Rendezvous & Historic Reenactment Resources

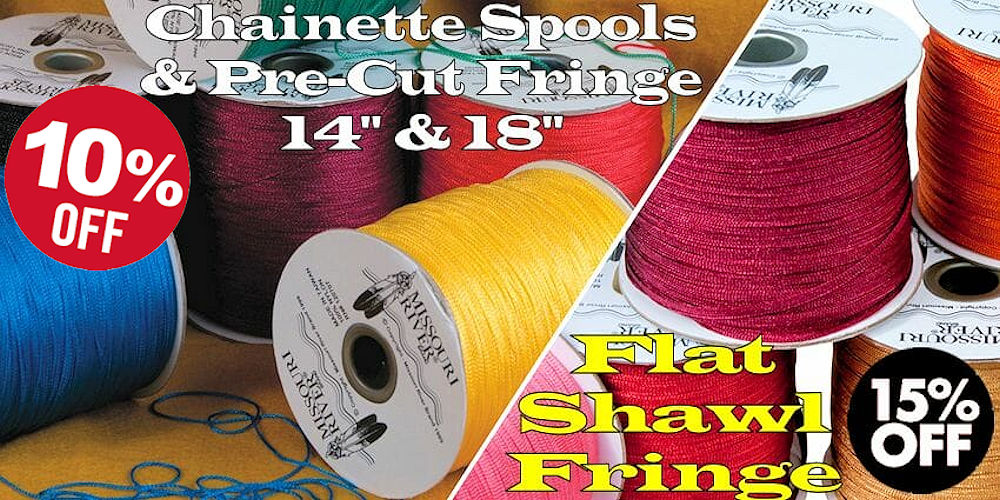

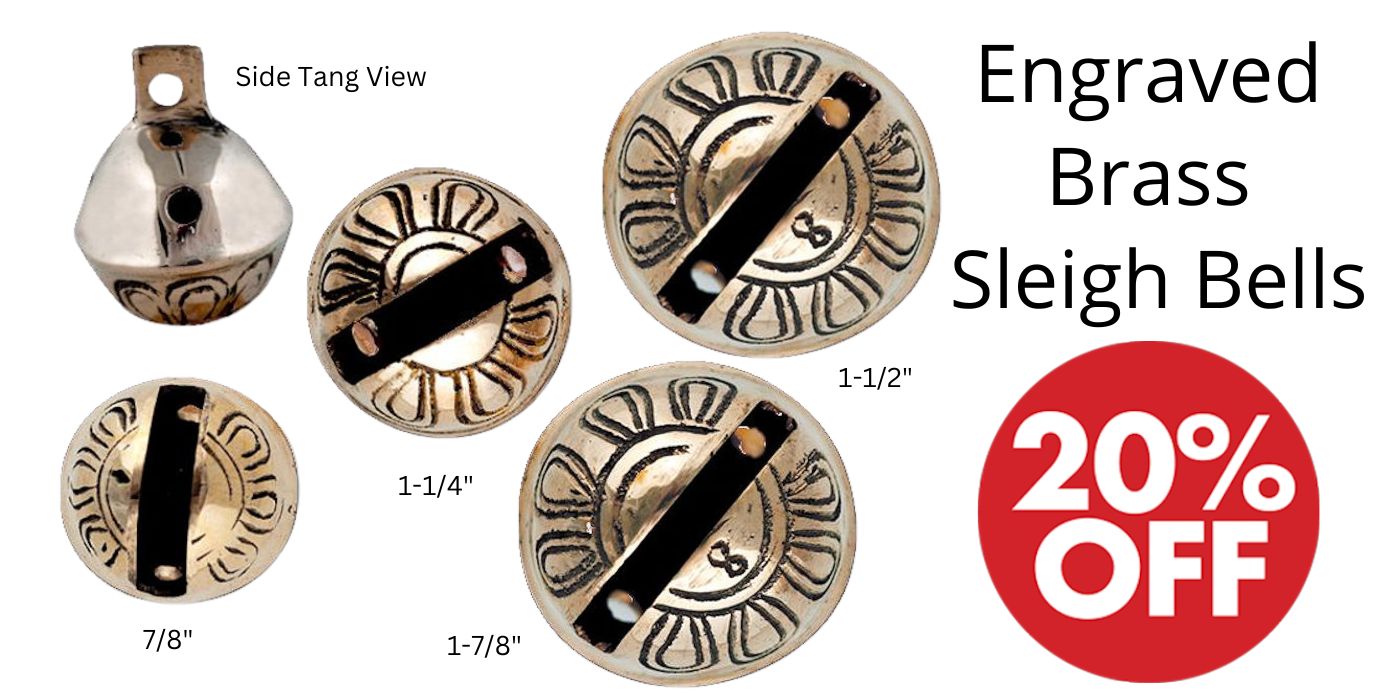

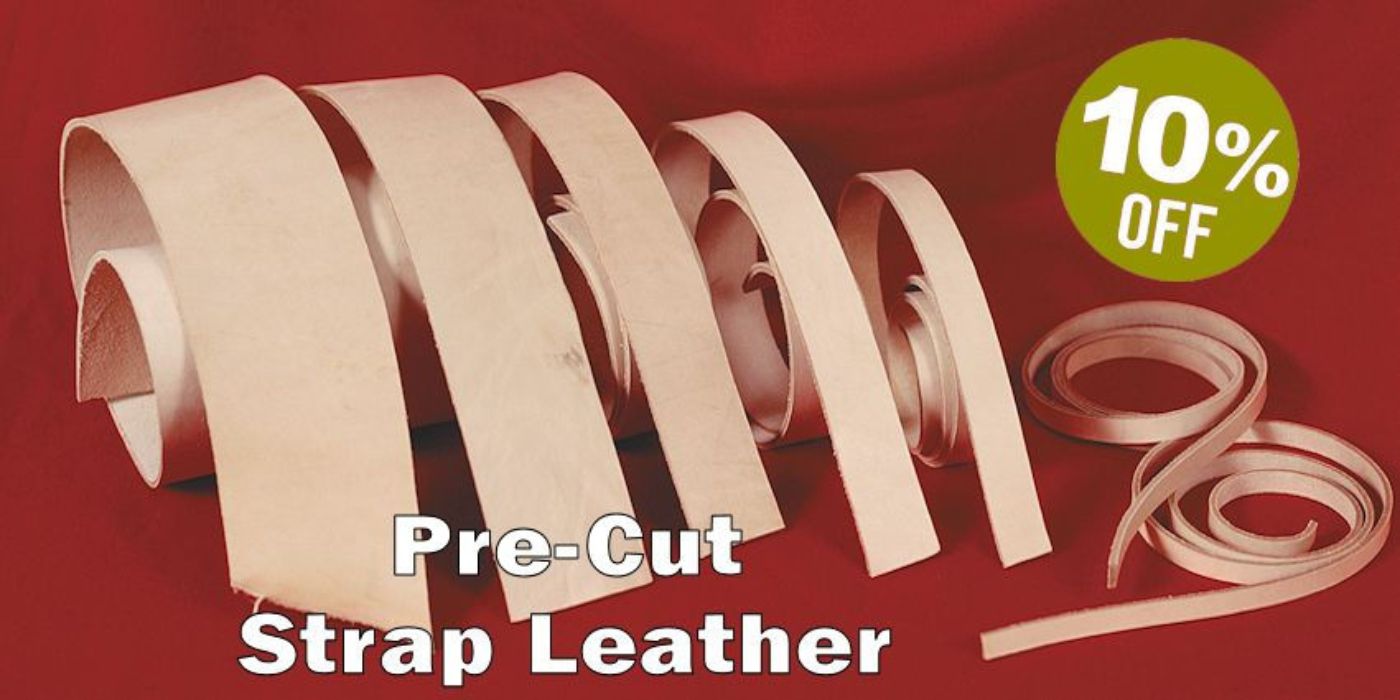

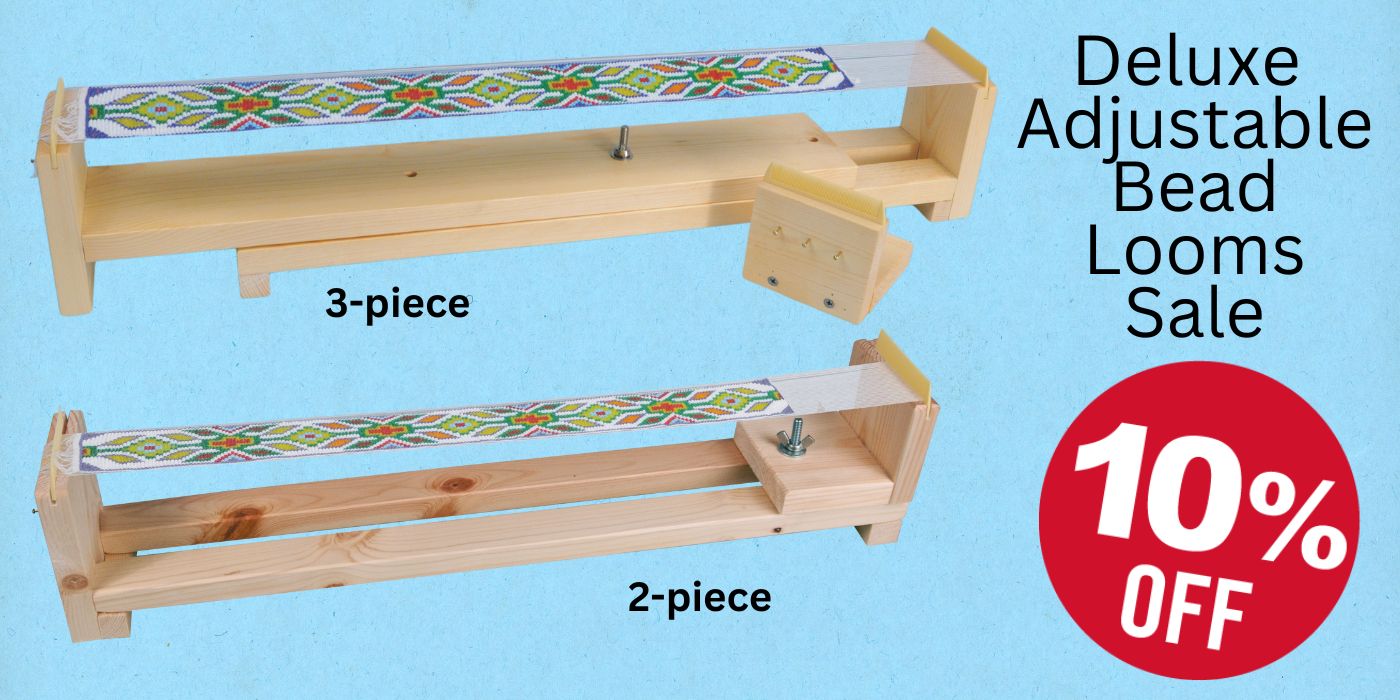

Current Crow Calls Sale

January – February

SAVE 10%-25% on popular powwow, rendezvous, historic reenactor, bead & leather crafter supplies. Crazy Crow is starting out the New Year with savings on many popular craft supply items like Plains Hard Sole Moccasin Kits, Chainette Spool and Pre-Cut 14 & 18 inch Fringe, Flat Spool Fringe, as well as big savings on very popular items like most types of our brass beads, artificial sinew, bone hair pipes, Peyote Kettles and Drum Covers, select hand-made Frontier Knives, and engraved brass sleigh bells. Of course you can order everything online 24×7.