James Wilkinson: America’s Forgotten Traitor

Pike’s Expeditions Under Wilkinson’s Command & their Influence

on the Fur Trade, Frontier Forts & Westward Expansion

By Crazy Crow Trading Post ~ October 1, 2025

James Wilkinson: America’s Forgotten Traitor

Pike’s Expeditions Under Wilkinson’s Command & their Influence

on the Fur Trade, Frontier Forts & Westward Expansion

By Crazy Crow Trading Post ~ October 1, 2025

In the annals of American history, few men wielded as much covert influence—and escaped as much accountability—as General James Wilkinson. Despite his obscurity in popular memory, Wilkinson’s career stretched across the French and Indian War, the Revolution, the War of 1812, and even the early years of the Monroe Doctrine. In each arena, his actions bent the trajectory of the young republic, frequently in ways that compromised its sovereignty.

Wilkinson’s legacy embodies contradiction. He ascended to the highest ranks—Senior Officer of the Army, Governor of the Louisiana Territory—yet for over three decades he secretly served as “Agent 13,” a salaried spy of the Spanish Empire. His duplicity ran so deep that Theodore Roosevelt later judged him “the most despicable character in American history.”

What makes Wilkinson’s story disturbing is not only the treason itself, but his uncanny ability to evade justice. He manipulated allies and enemies alike, cultivating trust in every quarter while serving two masters—the United States and Spain. His hand appeared in the Burr conspiracy, in plots to incite war with Mexico, and in nearly every major geopolitical intrigue of the early republic. To study Wilkinson is to see the vulnerabilities of a fragile nation laid bare: how easily personal ambition could bend the destiny of a republic still struggling for stability.

A general in sheep’s clothing sets the stage for decades of treachery.

Wilkinson’s betrayals were not just personal—it was structural. He exploited the very institutions designed to protect the republic, turning them into tools of subversion. His story is a cautionary tale about the dangers of concentrated power, unaccountable leadership, and the ease with which national trust can be weaponized against the nation itself.

The unique nexus of James Wilkinson’s professional authority, the trust placed in him by the highest offices of the early republic, and his secret personal and conspiratorial agenda had the potential to profoundly—and dangerously—alter the course of American history. Here’s how:

Wilkinson’s Conspiracy Goals: A Breakdown

Wilkinson’s Dual Role: Administrator and Saboteur

As Senior Officer of the U.S. Army, Governor of the Louisiana Territory, and a trusted figure under Presidents Washington, Jefferson, and Madison, Wilkinson was entrusted with safeguarding the frontier during a time of intense geopolitical tension. The U.S. was navigating:

Yet Wilkinson used this trust not to defend the republic, but to advance his own empire-building ambitions, often in direct service to Spain, where he was known as Agent 13.

What important government positions did Wilkinson attempt to leverage as a spy?

In the annals of American history, few men wielded as much covert influence—and escaped as much accountability—as General James Wilkinson. Despite his obscurity in popular memory, Wilkinson’s career stretched across the French and Indian War, the Revolution, the War of 1812, and even the early years of the Monroe Doctrine. In each arena, his actions bent the trajectory of the young republic, frequently in ways that compromised its sovereignty.

Potential Impacts on the Future of the United States

And now, for the story: “James Wilkinson: The Spanish Spy”

James Wilkinson (1757–1825) rose to the highest military and political offices of the early republic, serving under four presidents and twice holding the post of Senior Officer of the U.S. Army. He was the first Governor of the Louisiana Territory and moved in the circles of America’s most powerful leaders. Yet for over three decades he lived a double life as “Agent 13,” a salaried spy for the Spanish crown. His treachery was richly rewarded: annual pensions flowed to him, sometimes hidden in barrels of coffee and sugar. His treason remained shielded until 1854, when historian Charles Gayarré uncovered the Spanish archives in Madrid and confirmed what many had long suspected.

Wilkinson’s Revolutionary service placed him under Benedict Arnold during the Quebec invasion, where both men shared the humiliation of retreat in 1776. Shortly after, he attached himself to General Horatio Gates, only to be drawn into the Conway Cabal against George Washington. The plot collapsed, and Wilkinson’s loose tongue exposed it, forcing him to resign in disgrace. It was the first in a series of intrigues that defined his career.

By 1804, Wilkinson conspired with former Vice President Aaron Burr to carve out an empire in the American Southwest—perhaps including New Orleans and Spanish Texas. The partners exchanged coded letters, one of which Wilkinson later altered to disguise his own role while implicating Burr. When Jefferson demanded answers, Wilkinson alone could “translate” the cipher, ensuring his interpretation would shape the official record. Burr was tried for treason in 1807, but acquitted when Chief Justice John Marshall ruled that no overt act of war had been proven. Wilkinson’s credibility was shredded, yet he escaped conviction.

Wilkinson was not alone in seeking Spanish pensions. Among those touched by his proposals were prominent Kentuckians—federal judge Harry Innes, Benjamin Sebastian, U.S. Senator John Brown, Isaac Shelby, and others. Some were complicit, others merely deceived, but all found their reputations shadowed by Wilkinson’s schemes.

Though he lost the governorship and endured investigations—including a court-martial in 1811—he was never convicted. His failures in the War of 1812 sealed his reputation for incompetence. By 1815, he was discharged, drifting into obscurity before dying in Mexico City in 1825, still lobbying for influence. Only decades later did the Spanish archives reveal the full measure of his betrayal, cementing his place in history as Roosevelt’s “most despicable character.”

The Ciphered Letter and the Spanish Archive

In 1854, historian Charles Gayarré’s discovery of Spanish records in Madrid confirmed suspicions that had dogged Wilkinson for decades. The papers revealed the full scope of his treachery:

These revelations, published almost three decades after Wilkinson’s death, horrified Americans. They confirmed that the man entrusted with America’s western defense had in fact worked tirelessly to weaken it.

Wilkinson’s Attempt to Provoke War with Mexico

Wilkinson’s ambitions stretched beyond espionage. He sought chaos itself, hoping that a war with Spain would create the fog he needed to cloak his own schemes. Zebulon Pike, a young officer under his command, became an unwitting instrument in this effort.

For Wilkinson, war was opportunity. With American attention fixed on conflict, he could maneuver in the borderlands—perhaps seizing New Orleans, Texas, or Mexican provinces—under the guise of national defense.

In 1805, Pike was sent north to locate the Mississippi’s source—he misidentified it, but asserted U.S. presence. In 1806–07, Wilkinson dispatched him west, ostensibly to map rivers and make tribal contact. Unofficially, Pike’s orders served Wilkinson’s interest: testing Spanish strength and provoking confrontation. Pike sighted the mountain that now bears his name, wandered deep into Spanish Colorado and New Mexico, and pressed on until capture.

Spanish forces seized Pike and marched him over 1,000 miles to Chihuahua. There he observed fortifications, towns, and roads—intelligence later embedded in his journals. The Spanish eventually released him, treating him more as a guest than a prisoner, but they had no appetite for war.

Historians debate Pike’s awareness. Most believe he remained loyal and unsuspecting, dutifully carrying out orders without realizing the political trap he advanced. He returned with priceless intelligence, but also with a tarnished reputation for wandering into forbidden territory.

Jefferson resisted war with Spain, wary of overextension. The Burr conspiracy collapsed, robbing Wilkinson of cover. Spain, though alarmed, chose diplomacy over escalation. Wilkinson’s gambit failed.

In hindsight, Pike’s journeys mapped the southern Rockies and provided lasting knowledge of the Southwest. Yet they also reveal how easily honest service could be bent into the machinery of treason.

The Shadow Campaign: Wilkinson’s Black-Flag Ambitions

Before Zebulon Pike ever set foot in Spanish territory, Wilkinson had already envisioned what can best be described as a black-flag operation. This was not official U.S. policy but a personal, extra-national scheme to exploit the blurred lines of the frontier. His aim was audacious: to seize New Orleans, Spanish Texas, and perhaps swaths of Mexico, while concealing his intent behind the rhetoric of national defense.

Wilkinson met with leaders in Tennessee and Kentucky, urging them to ready their militias. He implied such mobilization had Washington’s blessing, when in reality it advanced his personal empire-building. Frontier men, believing they were preparing to defend the republic, were pawns in his ploy.

Into this shadow campaign walked Zebulon Pike. Sent under orders cloaked in legitimacy, Pike carried out explorations that doubled as reconnaissance. His journal—later confiscated by Spanish authorities—offered intelligence on terrain, tribes, and fortifications, which Wilkinson hoped to fold into his designs.

Wilkinson’s black-flag ambitions illustrate the danger of blurred sovereignty on America’s borderlands: where patriotism and treason could wear the same uniform, and where one man’s ambition threatened to drag nations into war.

Highlights from Pike’s Journal (1805–1807)

Pike’s first expedition, ordered by Wilkinson, sought to locate the source of the Mississippi River and establish a U.S. presence in the newly acquired Louisiana Territory. Though he misidentified the source, placing it farther south than its true location, the mission underscored America’s claim in the upper Midwest and laid the groundwork for forts and trade routes that would later support fur commerce.

His second mission took him into the Arkansas River Valley and beyond. Pike famously sighted the towering mountain that would bear his name, though he never reached its summit. Believing he was tracing the Red River, he actually entered Spanish Colorado and New Mexico. His trek revealed both the promise of the southern Rockies and the hazards of trespassing on Spanish soil.

In early 1807, Spanish troops arrested Pike near Alamosa, Colorado. Rather than harsh imprisonment, he and his men were escorted as “guest-prisoners” through Santa Fe, Chihuahua, and San Antonio. Pike marveled at the courtesy of officers like Lt. Don Facundo Malgares, though he also sensed surveillance and unease.

Pike’s maps and notes were seized, yet he secretly preserved his personal diary, smuggling it home. This survival of his firsthand record explains why his observations still reach us today.

His diary noted the poor state of medicine, the charm of Spanish women, and the rigid structure of colonial administration. He admired the hospitality but criticized Spain’s inefficiency, portraying New Spain as a land rich in potential but stifled by misrule.

Pike insisted his southern foray was accidental, but many doubted it. Spanish officials suspected espionage, and later historians have viewed the expedition as a calculated probe, convenient to Wilkinson’s ambitions.

Published in 1810, Pike’s journal became a bestseller, translated into several languages. It offered Europe and America a first-hand look at the southern Rockies and Spanish frontier. More than literature, it was intelligence: maps, sketches, and cultural notes that guided explorers, traders, and the fur companies that followed.

Bent’s Fort: Gateway of the Southern Fur Trade

Established in 1833 by William and Charles Bent and Ceran St. Vrain, Bent’s Fort rose along the Arkansas River at a site Pike had traversed a generation earlier. Its adobe walls soon housed a bustling multicultural hub: American trappers bartering buffalo robes, Mexican merchants hauling goods from Santa Fe, and Cheyenne and Arapaho exchanging horses, hides, and diplomacy.

Languages mingled—English, Spanish, French, Cheyenne, Arapaho. Famous figures like Kit Carson found employment there; Jim Beckwourth spun tales within its walls; John C. Frémont staged expeditions from its gates.

During the Mexican-American War, Bent’s Fort became a staging ground for U.S. forces moving south. Its position on the Santa Fe Trail gave it strategic weight beyond commerce.

By 1849, disease, falling trade, and shifting politics spelled its end. Yet its story endures: Bent’s Fort was both marketplace and meeting ground, a living monument to the way Pike’s reconnaissance of the Arkansas corridor opened paths that others transformed into empires of trade.

Northern Rocky Mountain Forts: Pike’s Distant Influence

Pike never set foot in Montana, Idaho, Wyoming, or northern Utah, yet his expeditions offered a template for what followed. By proving that U.S. officers could traverse and document the frontier, he paved the way for others to push deeper into the Rockies. His maps and journals gave confidence that the West, though daunting, was navigable.

While Pike’s trail lay far to the south, his work helped normalize the idea of military exploration feeding directly into commercial outposts.

Fort and Rendezvous Locations Relative to Pike’s Maps

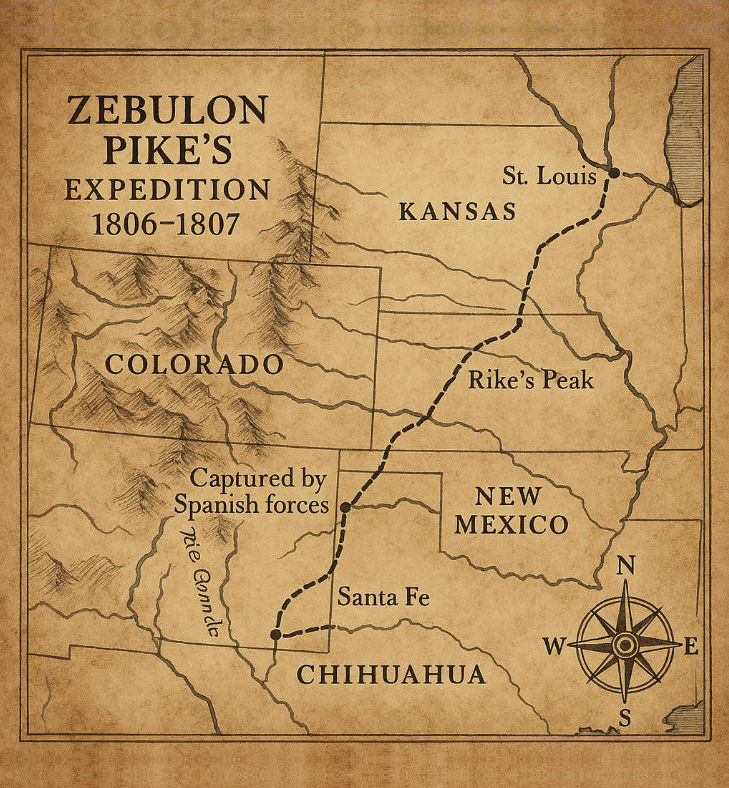

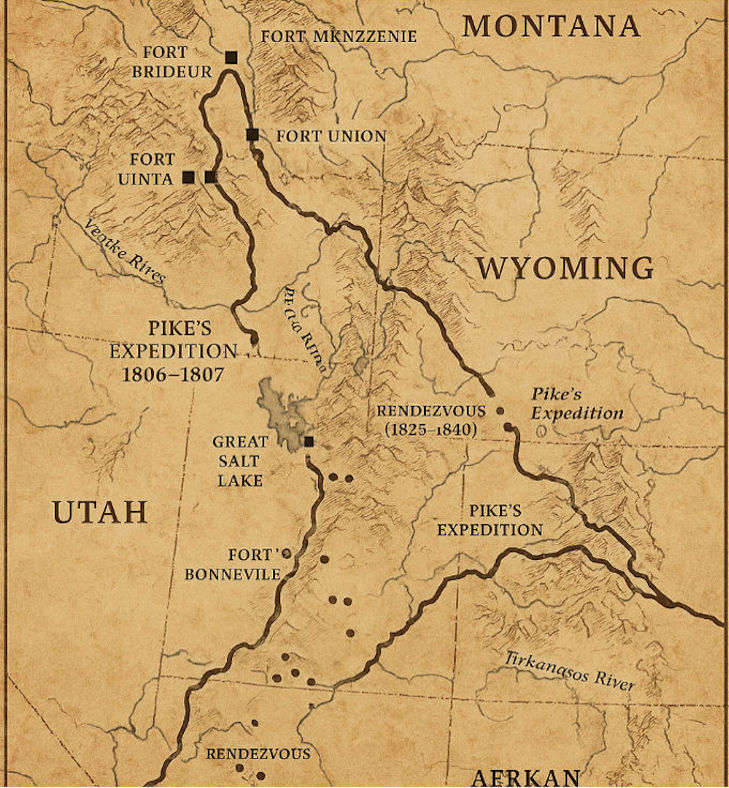

Two maps illustrate Pike’s legacy. The first overlays his 1806–07 routes with the fur trade forts later built in the Rockies, and the point he was captured by the Spanish (Wilkinson’s true intent). The second shows the Rocky Mountain Rendezvous sites of 1825–1840, plotted in Wyoming’s Green River Valley and Utah’s Bear Lake region

Rendezvous locations were chosen for proximity to the richest trapping grounds, for their distance from permanent forts, and for ease of caravan access. The Green River Valley, with its open meadows and convergence of trails, became the heart of the system.

By the late 1830s, two forces converged. Beaver were trapped to scarcity, and more decisively, fashion betrayed the trade. In Europe and America, silk toppers replaced beaver felt hats. Demand collapsed almost overnight.

Thus, the rendezvous system died not from lack of daring but from a shift in wardrobes. Pike’s routes lived on in permanent forts, but the annual carnival of mountain men became a relic of memory.

The Fashion Shift that Ended the Beaver Trade

In the late 1830s, gentlemen in Paris, London, and New York traded their felted beaver hats for sleek silk toppers. The change seemed trivial, yet it shattered an industry that stretched from the Rockies to the Seine.

The beaver hat had been a symbol of refinement and durability. When fashion decreed otherwise, its value evaporated. Traders who had depended on European demand found themselves holding pelts that no longer fetched profit.

Companies that once sent caravans into the mountains saw their margins collapse. Rendezvous dwindled, then ceased. Entire tribal economies that had been pulled into the fur trade felt the shock.

Thus, the collapse of style in European capitals reverberated across the American frontier, proving that cultural taste could carry the weight of economic fate.

Overtrapping and Fashion: Twin Causes of Collapse

The end of the beaver trade cannot be explained by fashion alone. Overtrapping devastated animal populations across the Rockies and Pacific Northwest. By the 1840s, habitats were exhausted. Yet even if streams had teemed with beaver, the market had already collapsed.

Fashion struck the final blow. With demand gone, there was no incentive to restrain hunting or rebuild populations. The ecology of the mountains and the tastes of Europe collided, producing a sudden and irreversible collapse.

As the beaver trade died, fur companies pivoted to buffalo robes and later to hides. Tribes who had been drawn into a global market found themselves scrambling to adapt. Forts shifted from fur depots to centers of robe trade and emigrant resupply.

Together, depletion and fashion ended the rendezvous system, and with it, an era of frontier commerce tied directly to Pike’s shadowed reconnaissance.

Pike’s Influence on America’s Westward Expansion

Pike’s journeys extended far beyond the fur trade. When his journals appeared in 1810, they gave Americans and Europeans alike a new picture of the continent’s interior.

For pioneers contemplating the move west, Pike’s sketches of rivers and valleys provided reassurance that the wilderness was knowable. His maps, though flawed, gave settlers confidence in navigation.

For the U.S. Army, Pike’s notes offered intelligence on Spanish strength, Native nations, and geographic choke points. His reconnaissance became strategic planning material.

Translated abroad, his journal showed Europe that the United States was already probing deep into contested territory. Pike thus became, unintentionally, an ambassador of expansionism.

Though he operated under Wilkinson’s shadow, Pike’s work became a cornerstone of the nation’s westward momentum.

Pike’s Influence on the American Fur Company and the Rendezvous System

John Jacob Astor’s American Fur Company, founded in 1808, thrived in part because Pike had already opened a window into the West.

When Pike’s journals appeared, they circulated among traders in St. Louis and New York. Astor’s agents could consult Pike’s descriptions of valleys, passes, and tribal nations when planning expeditions. Pike gave them a reconnaissance base that made their risky ventures seem manageable.

The annual mountain meetings, beginning in 1825, depended on knowing where caravans could safely travel and where trappers could congregate. Pike’s notes on accessibility, tribal relations, and seasonal weather informed these choices. Rendezvous organizers, knowingly or not, drew from Pike’s groundwork.

Pike, who never trapped a beaver, nonetheless became an architect of the systems that made the beaver trade flourish.

Pike’s Unintended Legacy

Pike marched under orders from James Wilkinson, a man whose treachery now defines infamy. Yet the lieutenant’s service produced consequences far greater than Wilkinson’s schemes.

Though Pike was a pawn in efforts to stir war or curry favor with Spain, his journals gave Americans knowledge that Wilkinson never intended them to have.

His maps guided trappers, his words inspired settlers, and his observations gave diplomats leverage. The empire he served tried to contain him; the republic he served reluctantly was empowered by him.

Thus Pike’s legacy is one of irony. Sent westward by a traitor’s hand, he returned with tools of nation-building. He proved that exploration, even when born of intrigue, can outlast betrayal and chart the course of a people.

Final Reflection: From Treason to Trade

At first glance, Zebulon Pike’s expeditions seem like footnotes to the larger dramas of Wilkinson’s treachery and Burr’s conspiracy. Yet their legacy far surpassed the intrigues that birthed them.

Wilkinson, Spain’s “Agent 13,” dispatched Pike as part of a shadow campaign. Burr’s schemes provided the backdrop. Both men sought personal empires. Pike, however, unwittingly produced something larger: a reconnaissance of the continent that would outlast both plotters.

The maps he sketched became scaffolding for rendezvous sites in Wyoming, forts in Colorado, and caravan routes to Santa Fe. Traders like Ashley, Smith, Bridger, and Carson followed paths Pike had first described under duress.

His capture by Spanish authorities turned him into a reluctant envoy. His journals, seized and scrutinized, revealed Spain’s vulnerabilities even as they documented its strengths. Later American negotiators, soldiers, and settlers leaned on Pike’s words as much as his lines on a map.

Pike’s legacy, then, is one of unintended consequence. Sent westward by a traitor’s hand, he returned with knowledge that strengthened a republic. His expeditions became a hinge: transforming treasonous intrigue into the foundation of trade, settlement, and expansion.

Rendezvous & Historic Reenactment Articles

Rendezvous & Historic Reenactment Resources

Current Crow Calls Sale

January – February

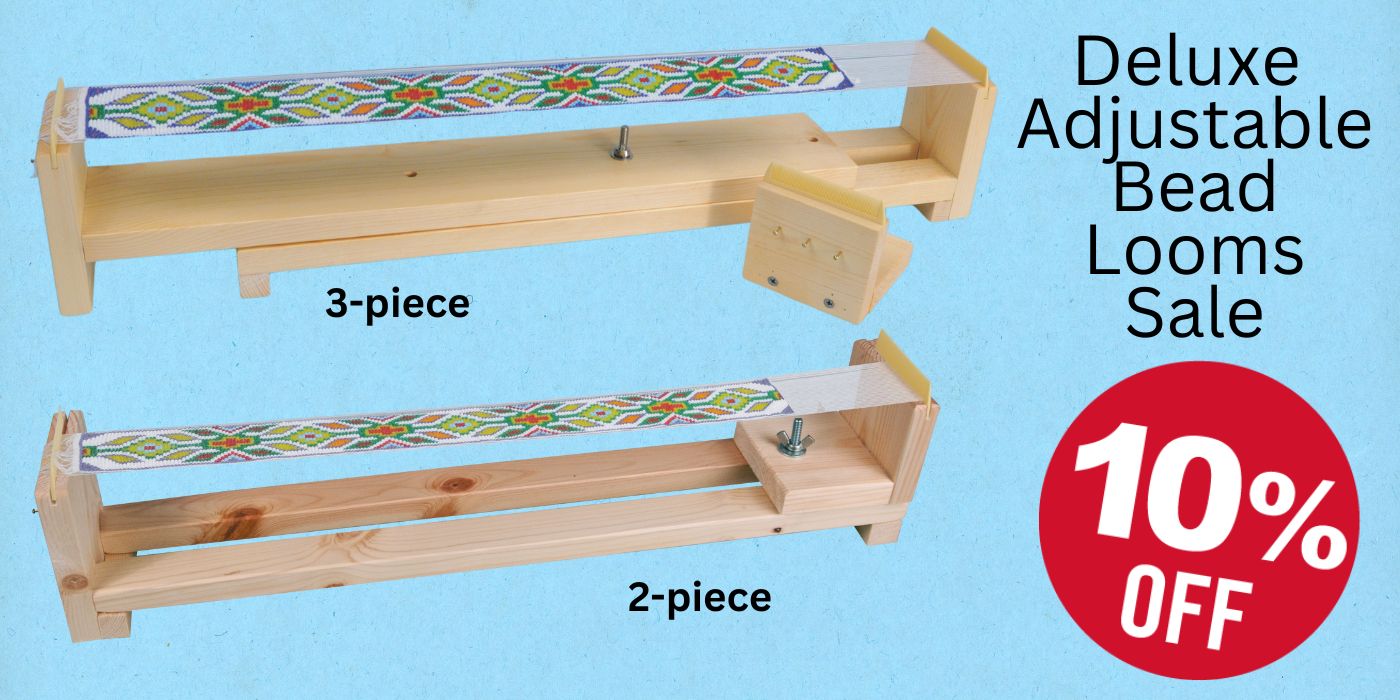

SAVE 10%-25% on popular powwow, rendezvous, historic reenactor, bead & leather crafter supplies. Crazy Crow is starting out the New Year with savings on many popular craft supply items like Plains Hard Sole Moccasin Kits, Chainette Spool and Pre-Cut 14 & 18 inch Fringe, Flat Spool Fringe, as well as big savings on very popular items like most types of our brass beads, artificial sinew, bone hair pipes, Peyote Kettles and Drum Covers, select hand-made Frontier Knives, and engraved brass sleigh bells. Of course you can order everything online 24×7.