What is the Difference in a Mountain Man Rendezvous

a and Voyageur Rendezvous?

The North American Fur Trade: Timeline, Transitions, and Tribal Impacts

By Crazy Crow Trading Post ~ Updated May 12, 2025

What is the Difference in a Mountain Man Rendezvous and Voyageur Rendezvous?

The North American Fur Trade: Timeline, Transitions, and Tribal Impacts

By Crazy Crow Trading Post ~ Updated May 12, 2025

When most people hear “rendezvous,” they often picture the rugged mountain men of the American West—bearded, buckskin-clad trappers gathering in a festive wilderness carnival. These Rocky Mountain Rendezvous, held annually from 1825 to 1840, indeed form a dramatic chapter in American frontier history. But they represent only a fraction of the North American fur trade’s long and complex story.

In contrast, the Voyageur Rendezvous—centered in the Great Lakes and Canadian Shield—spanned nearly two centuries. French traders, Indigenous nations, and later British and Métis participants engaged in an extensive fur trading network that was both more enduring and more deeply interwoven with Native life than its Western Rocky Mountains counterpart. These gatherings were held regularly between the 1730s and early 1800s, with some activity dating back as far as the mid-1600s.

Click to enlarge any image.

Grand Portage Voyageur Rendezvous

Click to enlarge image.

Grand Portage Powwow

Public Memory & Reenactments: “Rocky Mountain Rendezvous” Events Overshadow “Voyageur Rendezvous”.

Despite the greater longevity and geopolitical reach of the Voyageur trade, modern rendezvous calendars (including those once maintained by Crazy Crow Trading Post) and others reveal a striking bias: Mountain Man–style reenactments vastly outnumber those reflecting the Voyageur heritage. We should also add that, while there are quite a number of rendezvous in the states surrounding the Great Lakes, including Ohio on the eastern side, you are more likely to see individuals in the Rocky Mountain era dress at those events.

However, this imbalance doesn’t reflect the historic breadth of the fur trade. In fact, the earliest North American fur trading hubs were Eastern, concentrated in areas now known as Michigan, Ontario, Minnesota, and Quebec. Places like Grand Portage, MN were critical rendezvous points during the French and British regimes. When the British were expelled following the American Revolution, they relocated their northern operations to Fort William in present-day Thunder Bay, Ontario, just 75 miles north.

Probably the largest Voyageur rendezvous held today is the annual Grand Portage Rendezvous Days on the second weekend each August at the Grand Portage Monument Heritage Center in Grand Portage, Minnesota. Explore the reconstructed 1790s fur trade depot and the historic voyageurs’ encampment. Watch (or join) three days of rendezvous activities.

Bonus activity: adjacent to the rendezvous, hundreds of participants will take part in the Grand Portage Rendezvous Days Celebration Pow Wow (aka Grand Portage Powwow). This powwow is sponsored by the Grand Portage Band of Lake Superior Chippewa. Watch or join in with hundreds of Native American dancers. Follow the links for more detail.

Why here? About The Grand Portage: The Grand Portage is an 8.5-mile historic trade route of the French-Canadian voyageurs that passes through waterfalls and rapids that flow into Lake Superior. It became the gateway into rich northern fur-bearing country, where it connected remote interior outposts to lucrative international markets. In August every year from the early 1700s to about 1803, the voyageurs would show up and the company owners would come from Europe, and Grand Portage became a rough and tumble celebration. After the celebration, the furs were loaded aboard massive voyageur canoes and paddled across the Great Lakes and eventually shipped to Europe where many became hats. In the states, the voyageurs would carry trade goods up the portage and then paddle 100s of miles back to their outposts. This repeated until beaver was almost extinct. Luckily for the beaver, the fur hats that their pelts were used went out of fashion.

Click to enlarge image.

Nikki Rajala’s Voyageur Blog

Giving the Voyageur Rendezvous Their Due

At Crazy Crow, we recognized this historical imbalance and, beginning in the late 2000s, when we were maintaining the largest rendezvous calender in North America, we chose to split our rendezvous listings into two core categories:

- Eastern Longhunters & Voyageur Rendezvous

- Western Buckskinner / Mountain Man Rendezvous

By separating them, we hoped to better reflect their distinct cultural and geographic roots, while also supporting more accurate and inclusive reenactment communities.

Still, finding high-quality resources on Voyageurs and Voyageur Rendezvous remains challenging. Fortunately, researchers like Nikki Rajala, who runs a dedicated Voyageur blog from Minnesota, have begun filling that gap. Her firsthand family connections, archival discoveries, and storytelling lend much-needed life to this often-overlooked era.

About Crazy Crow Trading Post’s Rendezvous (powwow and historic reenactor) Event Calendars: Unfortunately, due to increasing costs, we stopped updating these calendars a few years ago. However, we kept the pages active as information on past events may help you contact the sponsors for new information concerning those or other events.

Click to enlarge image. Event & Photo Credit:

Des Plaines Valley Rendezvous

“A River Runs Through It”

Who Were the Voyageurs

The voyageurs (French for “travelers”) were the blue-collar backbone of the Montreal-based fur trade, from the 1680s until the 1870s. At their peak in the 1810s, more than 3,000 men paddled birchbark canoes through treacherous rivers, hauling heavy packs of trade goods and beaver pelts.

Drawn largely from rural French Canadian villages, these men were mostly illiterate, tough, and fiercely proud. They worked grueling 16-hour days, paddling 40–60 strokes per minute, carrying two 90-pound bundles on portages, and enduring disease, injury, and isolation. Twelve beaver pelts was an average man’s wage for an entire year.

These men agreed to work for a number of years in exchange for pay, equipment, clothing and “room and board.” Most voyageurs would start working when they were in their early twenties and continue working into their sixties. Sometimes being a voyageur was a family tradition.

Though often romanticized in song and folklore, Voyageurs were regarded as legendary, especially in French Canada, where they were considered heroes and celebrated in folklore and music. However, despite their fame, their lives were typically brutal, not as glorious as folk tales make it out to be. Danger was at every turn for the voyageur, not just because of exposure to outdoor living, but also because of the rough work.

Hernias were common and frequently caused death. Other physical ailments included broken limbs, compressed spine, rheumatism, and death by drowning were all common. Black flies and mosquitoes that plagued them were kept away from the sleeping men by a smudge fire that often caused respiratory issues, sinus and eye problems.

Written records are rare. The only known document left behind for posterity by a voyageur was penned by John Mongle who belonged to the parish of Maskinonge. He most likely used the services of a clerk to send letters to his wife. These chronicle his voyages into mainland territories in quest of furs.

Yet their legacy endured in Indigenous languages, trade routes, and even the rise of the Métis Nation—born from unions between voyageurs and Native women, especially Cree and Ojibwe.

Origins and End of the French Fur Trade & Voyageur Rendezvous

The rendezvous evolved from informal gatherings in the 1650s to structured events around forts like Michilimackinac. They ended by 1763 after the French defeat in the Seven Years’ War.

- 1650s: French traders and Indigenous allies establish Great Lakes trade routes, creating a need for centralized meetings.

- 1670s: Trading posts like Fort Michilimackinac support seasonal rendezvous.

- 1681: Formal licensing of coureurs des bois helps organize rendezvous culture.

- 1730s–1760: Annual gatherings in places like Grand Portage become vital hubs.

- 1763: Treaty of Paris ends French political control; British take over fur trade operations.

- Post-1763: British shift rendezvous north to Fort William after U.S. independence.

French Fur Trade Era: Indigenous Displacement, Conflict, and Trade Goods

- Huron-Wendat, Ottawa, and Algonquin tribes allied with French for early trade.[2]

- Comanche and Sioux combined horses and guns for dominance.[11]

- Iroquois pushed out rivals in the Beaver Wars.[12]

- Ojibwe expelled the Dakota from northern Minnesota.[13]

- Shoshone avoided armed Sioux despite having horses.[7]

- The Métis emerged from fur-trade intermarriage.[14]

For an overall and much more detailed review of the impact of the entire fur trade era (French voyageur era, Rocky Mountain rendezvous era, and Southwest fur trade) be sure to read the closing paragraphs of this article: Epilogue: What the Fur Trade Left Behind.

Two Traditions, One Shared Legacy

While the Voyageur and Mountain Man rendezvous traditions were separated by centuries and geography, they shared one key feature: the centrality of Indigenous nations. From the Algonquin and Ojibwe in the east to the Shoshone and Crow in the west, Native peoples were never passive actors. They were guides, trappers, traders, diplomats—and sometimes rivals—who shaped the terms of exchange, war, and survival on the frontier.

Both traditions are worthy of recognition. And with renewed attention to source accuracy, tribal impacts, and intercultural cooperation, we can better honor the complexity of these gatherings—not just as colorful reenactments, but as living histories.

The Mountain Men and their Short-Lived Rendezvous Era (1825-1840)

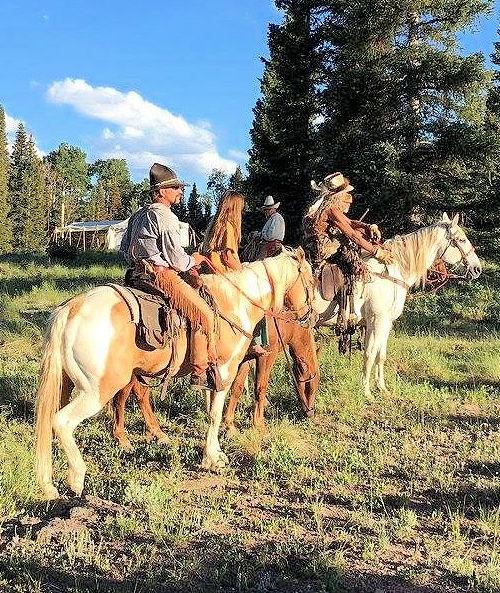

Click to enlarge image. Photo Credit: Hugo Dale

By comparison, the Rocky Mountain rendezvous era was brief—just 16 years between 1825 and 1840. Launched by General William Ashley and the Rocky Mountain Fur Company, these annual events served as mobile supply depots and social hubs in the wilderness.

Held in places like Horse Creek (WY), Pierre’s Hole (ID), and Cache Valley (UT), the rendezvous attracted free trappers, company men, Plains tribes, and Euro-American adventurers. James Beckwourth, a mixed-race mountain man, famously described them as wild festivals of “mirth, songs, dancing, shooting, racing, and frolic.”

These Western rendezvous were more than trade fairs—they were spectacles, sometimes drawing 500 trappers and thousands of Native participants. They mirrored the rapid, exploitative surge of Western expansion: short-term, high-reward, and destined to collapse under its own weight by the 1840s as beaver populations declined and silk replaced felt hats.

First Rocky Mountain Rendezvous

General William Ashley’s men of the Rocky Mountain Fur Company started the tradition of the rendezvous in 1825. What began as a practical gathering to exchange pelts for supplies and reorganize trapping units evolved into a month long carnival in the middle of the wilderness. The gathering was not confined to trappers, and attracted women and children, Indians, French Canadians, and travelers. Mountain man James Beckworth described the festivities as a scene of “mirth, songs, dancing, shouting, trading, running, jumping, singing, racing, target-shooting, yarns, frolic, with all sorts of extravagances that white men or Indians could invent.” An easterner reported that: “mountain companies are all assembled on this season and make as crazy a set of men I ever saw.” There were horse races, running races, target shooting and gambling. Whiskey drinking accompanied all of them.

Click to enlarge image. Photo Credit: Hugo Dale

Click to enlarge image. Photo Credit:

Carol M. Highsmith; Inside the reconstructed Bridger Trading Post stockade.

Click to enlarge image. Photo Credit:

Carol M. Highsmith; “Mountain man” Jim Bridger’s trading post and stockade.

The ‘modern’ Fort Bridger Rendezvous, held annually on the Labor Day weekend, is a historical reenactment celebrating the mountain man fur trade era. While Jim Bridger did not build his Bridger’s Trading Post on the exact site of any of the 16 rendezvous, the 1825 site at Henry’s Fork is only 57 miles distant; and the 1833, 1835-1837, 1839-1840 Horse Creek site is 107 miles. Today’s Fort Bridger Rendezvous is held on the grounds of the reconstructed trading post and fort, blending historical interpretation with public engagement. Current Fort Bridger Rendezvous Website

Buckskinner / Mountain Man Rendezvous

Rendezvous held in the western part of what is now the United States included a more diverse range of activities than their northern Voyageur Rendezvous counterparts. Such a rendezvous might include several fur trading companies, and array of fur traders, mountain men and Native Americans. A substantial amount of deal-making and trading occurred at these rendezvous. These were often a temporary “town” of sorts with businesses which offered the fur trade workers and participants ways to spend their money on supplies and revelry. The North American fur trade in the west is identified with these large annual Mountain Man rendezvous that were held in various Rocky mountain locations from 1825 until 1840. One of the largest of these was the Rendezvous of 1832. Much of the attendance of these consisted of mountain men who were fur trade participants who were experienced at living in the mountain back country.

Between Rendezvous

After their rendezvous, these mountain men headed off to their fall trapping grounds. Contrary to the common image of the lonely trapper (the free trapper), the mountain men usually traveled in brigades of 40 to 60, including camp tenders and meat hunters (think of the movie, “The Revenent”). From these brigade base camps, they would trap in parties of two or three. It was then that the trappers were most vulnerable to Indian attack. Indians were a constant threat to the trappers, and confrontation was common. The Blackfeet were by far the most feared, but the Arikaras and Comaches were also to be avoided. The Shoshone, Crows and Mandans were usually friendly, however, trust between trapper and native was always tenuous. Once the beaver were trapped, they were skinned immediately, allowed to dry, and then folded in half, fur to the inside. Beaver pelts, unlike buffalo robes, were compact, light and very portable. This was essential, as the pelts had to be hauled later to rendezvous for trade. It is estimated that 1,000 trappers roamed the American West in this manner from 1820 to 1830, the heyday of the Rocky Mountain fur trade and Mountain Man / Buckskinner Rendezvous.

In November when the streams froze, the fur trapper, like the grizzly bear, went into hibernation. Trapping continued only if the fall had been remarkably poor, or if they were in need of food. Life in the winter camp could be easy or difficult, depending on the weather and availability of food. The greatest enemy was quite often boredom. The men would engage in many of the same rendezvous activities to fill the time, such as physical contests, card playing, checkers and dominos, tell stories, sing songs and read.

Rocky Mountain Rendezvous Locations

Thirteen of the sixteen Rocky Mountain Rendezvous were held west of the Continental Divide (1829, 1830, and 1838 were the exception). Six of the sixteen rendezvous were held in territory belonging to Mexico. Except the 1826-27-28 rendezvous in Utah and the 1832 in Idaho, all of the rendezvous were held in Wyoming. Six of the sixteen rendezvous were held on Horse Creek in the Green River Valley near present-day Daniel, Wyoming. There was no general rendezvous in 1831.

After the first rendezvous in 1825, the locaton of the next rendezvous was selected during the rendezvous. Selected sites were in a lush valley big enough for up to 500 mountain men, several thousand Indians, and grazing and water for thousands of horses. Members of the Shoshone, Crow, Nez Perce, and Flathead nations attended most of these rendezvous. Accessibility to supply trains from St. Louis was another important consideration in the site selection.

Rendezvous sites were not one central camp, but could spread out for miles. Rendezvous campsites were grouped around the various suppliers and companies, so depending on the number of suppliers, the overall site would vary.

Mountain Man Rendezvous Camp Locations (1825-1840)

NOTE: Links reflect current Rendezvous in these same locations each year. The “1838 Mountain Man Rendezvous” at the Wind River Heritage Center in Riverton, Wyoming is the only reenactment on the actual untouched, historic site where the rendezvous took place. Other rendezvous with link take place within a few miles of the original sites.

Epilogue: What the Fur Trade Left Behind

Timeline: Major Events in the Fur Trade (1530s–1850s)

- 1534: Jacques Cartier explores the Gulf of St. Lawrence; beginning of French claims.[1]

- 1608: Samuel de Champlain founds Quebec; alliance with Algonquin, Huron-Wendat, and Montagnais tribes.[2]

- 1670: Hudson’s Bay Company (British charter) challenges French dominance.[3]

- 1713: Treaty of Utrecht gives Britain major territory.[4]

- 1754–1763: French and Indian War.[5]

- 1783: Treaty of Paris (American Revolution).[6]

- 1804–1806: Lewis and Clark document Indigenous trade tensions.[7]

- 1821: HBC merges with North West Company.[8]

- 1840: Last Rocky Mountain Rendezvous.[9]

- 1850s: Reservation policy impacts begin.[10]

American Fur Trade Impact on Indigenous Peoples: Migration, Conflict, and Change

From start to finish, the fur trade profoundly affected Indigenous peoples of North America – economically, territorially, and politically. Demand for furs tied many Native nations into global markets: some groups grew powerful middlemen or suppliers, while others were displaced or destroyed.

Economic Dependency: Many nations became dependent on European trade goods. The Five Nations Iroquois, for example, grew reliant on firearms and metal tools obtained via trade, which in turn pushed them to hunt more and fight neighbors to control hunting territories. Across the continent, traditional crafts and subsistence patterns changed – why knap stone arrowheads when steel knife blades were available? Why maintain large crop fields when European sugar and bread could be traded for with furs? Over time, this dependency could undermine self-sufficiency and make Indigenous groups vulnerable if trade was disrupted.

Territorial Shifts: The fur trade triggered major migrations and realignments of tribal territories. In the Great Lakes region, the Iroquois wars of the 17th century pushed tribes like the Huron-Wendat, Ottawa, and Potawatomi westward. Sioux (Dakota) bands, once forest dwellers in Minnesota, moved onto the open Plains by the eighteenth century, partly due to pressure from the Ojibwe (who had guns from the French) and the allure of buffalo and horses. The Cheyenne similarly migrated from the Great Lakes to the Plains, transforming from agricultural villagers into nomadic buffalo hunters by the early 1800s – and eager trading partners at posts like Bent’s Fort. The Shoshone and Ute in the Rockies were displaced from some areas by the better-armed Blackfeet and Crow who traded for guns. In the Southwest, Apache and Navajo raids on Spanish settlements were intensified by competition over livestock (itself a side effect of Spanish ranching economy, which was partly sustained by trade in hides/tallow). We also see new multi-ethnic communities emerging: the Métis on the northern plains, as well as “villages” around trading posts where members of different tribes and mixed families settled (e.g., at Fort Union or Fort Vancouver, employees and native wives formed little communities).

Intertribal Relations: The influx of guns and horses via trade revolutionized intertribal warfare. Some groups gained deadly advantages – e.g., the Cree and Assiniboine, armed by the French and English, expanded west and north, displacing weaker neighbors. The Comanche, after acquiring Spanish horses in the 1700s, became dominant raiders and traders in the Southern Plains, controlling the flow of goods (including captives and mustangs) to New Mexico. On the other hand, tribes that lost access to firearms (due to being enemies of trading nations) often suffered: the Blackfeet initially had firearms from British traders and held off the Shoshone; when Americans (initially allied with Shoshone) didn’t trade guns to the Blackfeet, conflict erupted. Complex alliances formed and shifted based on trade access – Huron and Algonquins allied with French vs. Iroquois with English; Crow allied with Americans vs. Blackfeet with British; Pueblo Indians allied with Spanish vs. Navajo/Comanche raiders; and later, Plains tribes allied or opposed to the U.S. based on whether forts supplied them.

Cultural Changes: Many Indigenous communities adapted creatively. Métis culture blossomed – with unique music, dress (the Métis sash), and economic specialization (like the Red River cart brigades). Some tribes like the Ojibwe shifted their seasonal rounds to prioritize winter trapping for fur, altering gender roles (men trapping, women processing pelts and adapting crafts like beadwork using imported beads – which all glass beads were). Missionaries often followed traders, leading to religious changes (e.g., some Cree and Métis adopted Christianity through missionary influence at trade posts). However, not all changes were voluntary – disease was an uninvited consequence of trade contact. The smallpox epidemics of 1770s, 1837, and the cholera of 1849 killed tens of thousands of Indigenous people from the Missouri Valley to the Rockies, causing societal collapse in some cases (the 1837 smallpox outbreak at Fort Union nearly annihilated the Mandan and badly hit the Blackfeet, Arikara, etc., weakening their hold in the trade).

Conflict and Resistance: As the fur trade era waned and was replaced by outright colonial expansion, many tribes resisted the new order. Tecumseh’s War (1811) and Red Cloud’s War (1866–68), though separated by decades, both had roots in defending lands opened by earlier trade then threatened by settlers. The end of the fur trade often meant the beginning of open conquest. For instance, the Sioux, Cheyenne, Arapaho – once trading partners at Fort Laramie and Bent’s Fort – would in the 1860s fight against U.S. forts being built on their lands (leading to conflicts like the Sand Creek Massacre and Battle of Little Bighorn in the 1860s-70s, beyond the fur trade period being discussed). In Canada, Métis resistance flared in the Red River Rebellion (1869) and Northwest Rebellion (1885) as the HBC era gave way to Canadian Confederation.

In summary, Indigenous peoples were not passive in the fur trade – they were primary actors whose decisions shaped the course of history. Some groups prospered for a time by leveraging trade (e.g. Iroquois in 1600s, Comanche in 1700s, Métis in early 1800s), but most paid a steep price, whether through resource depletion, disease, or loss of independence. The fur trade changed native North America forever – by 1850s, the map of tribal territories was drastically different from that of 1500, and many cultural practices had evolved due to 300 years of exchange.

Tags: Difference in a Mountain Man Rendezvous and Voyageur Rendezvous, Mountain Man Rendezvous, Voyageur Rendezvous

View Past Voyageur Rendezvous or Encampment Events (reference only)

View Past Buckskinner & Mountain Man Rendezvous Events (reference only)

Map: Fur Trade Routes & Indigenous Movements

References and Resources

Rendezvous & Historic Reenactment Articles

Rendezvous & Historic Reenactment Resources

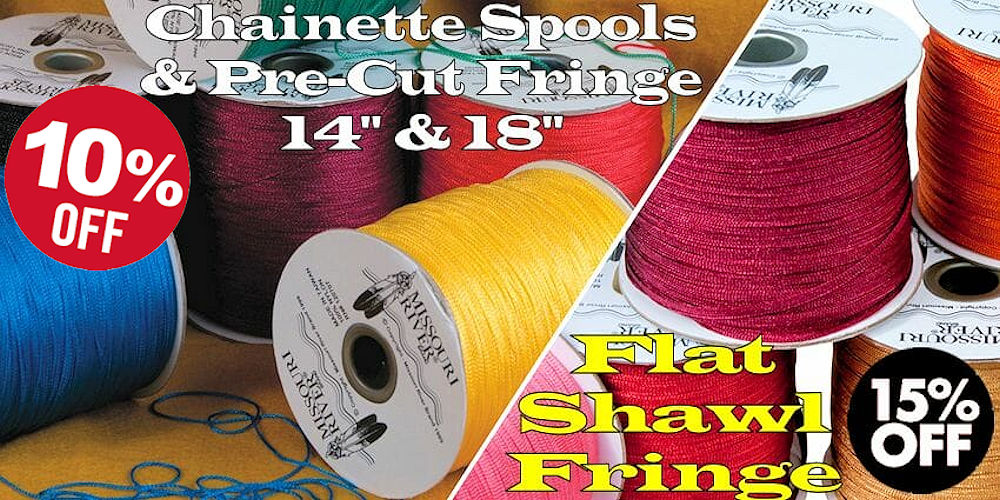

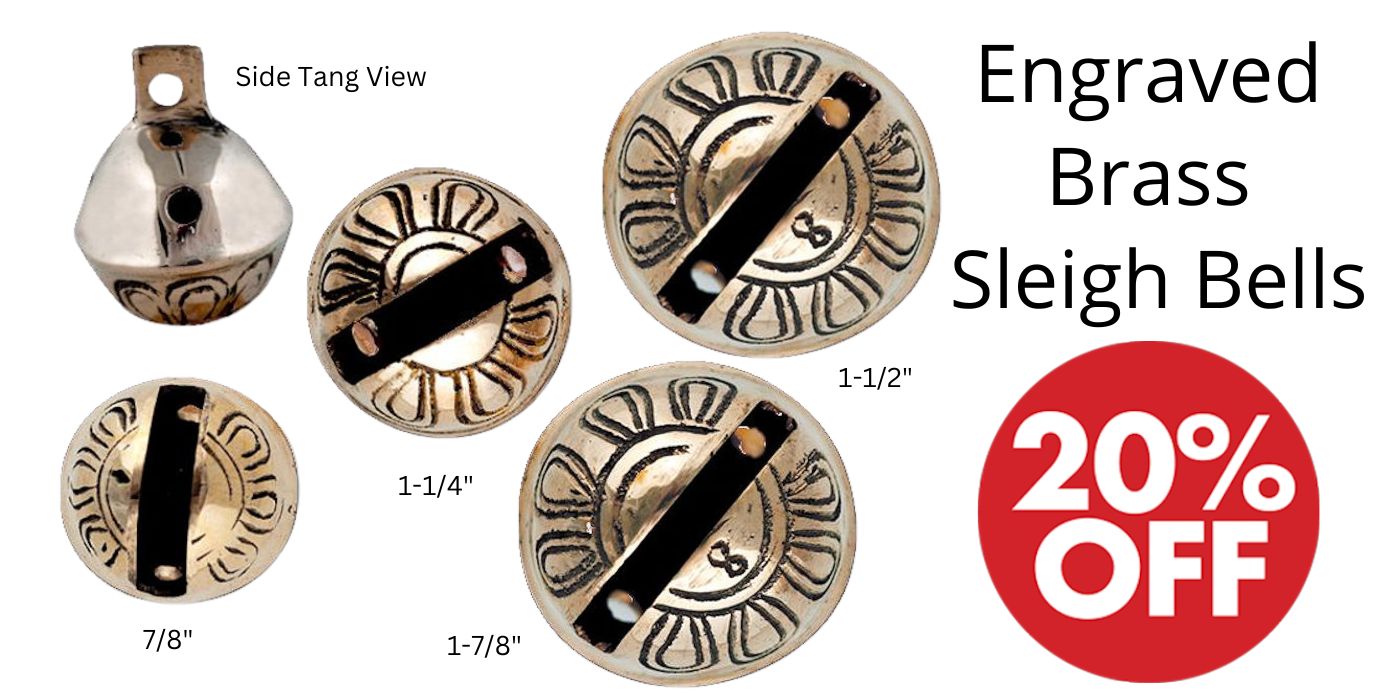

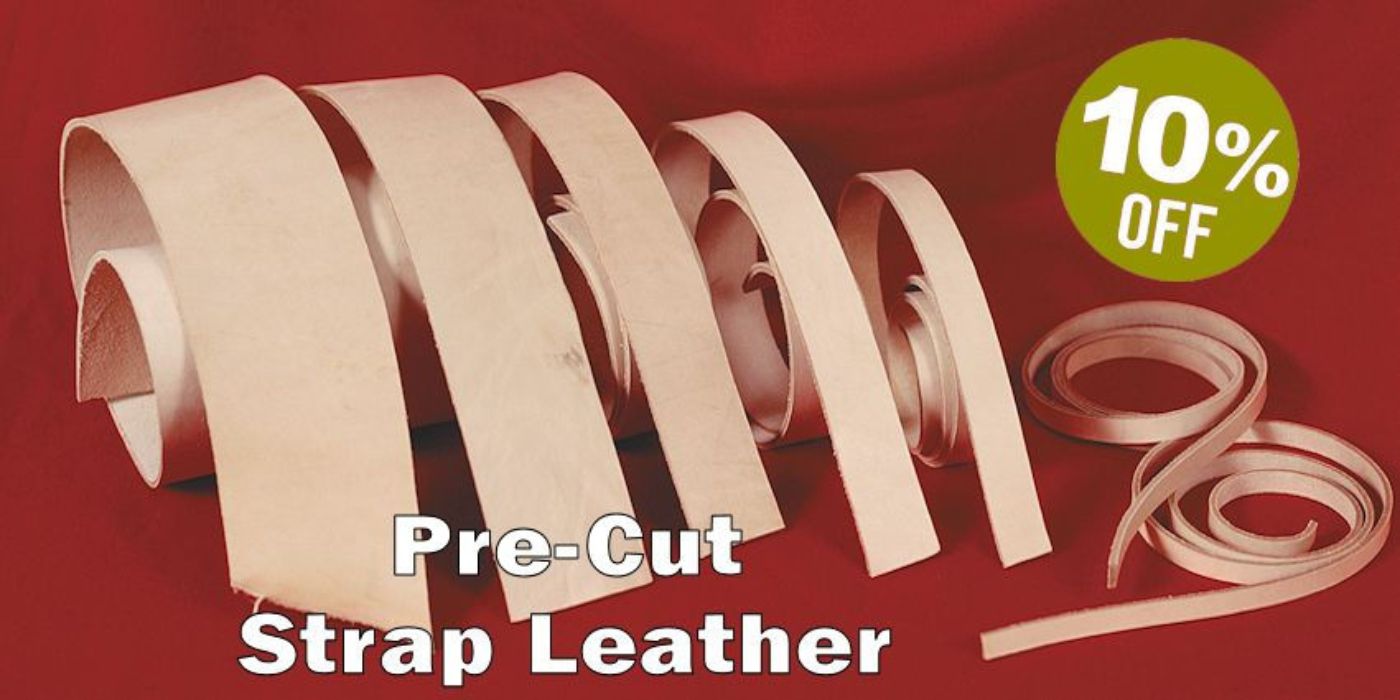

Current Crow Calls Sale

January – February

SAVE 10%-25% on popular powwow, rendezvous, historic reenactor, bead & leather crafter supplies. Crazy Crow is starting out the New Year with savings on many popular craft supply items like Plains Hard Sole Moccasin Kits, Chainette Spool and Pre-Cut 14 & 18 inch Fringe, Flat Spool Fringe, as well as big savings on very popular items like most types of our brass beads, artificial sinew, bone hair pipes, Peyote Kettles and Drum Covers, select hand-made Frontier Knives, and engraved brass sleigh bells. Of course you can order everything online 24×7.