The Beads That Did Not Buy Manhattan Island

Setting History Straight

By Peter Francis, Jr. with Commentary by Crazy Crow

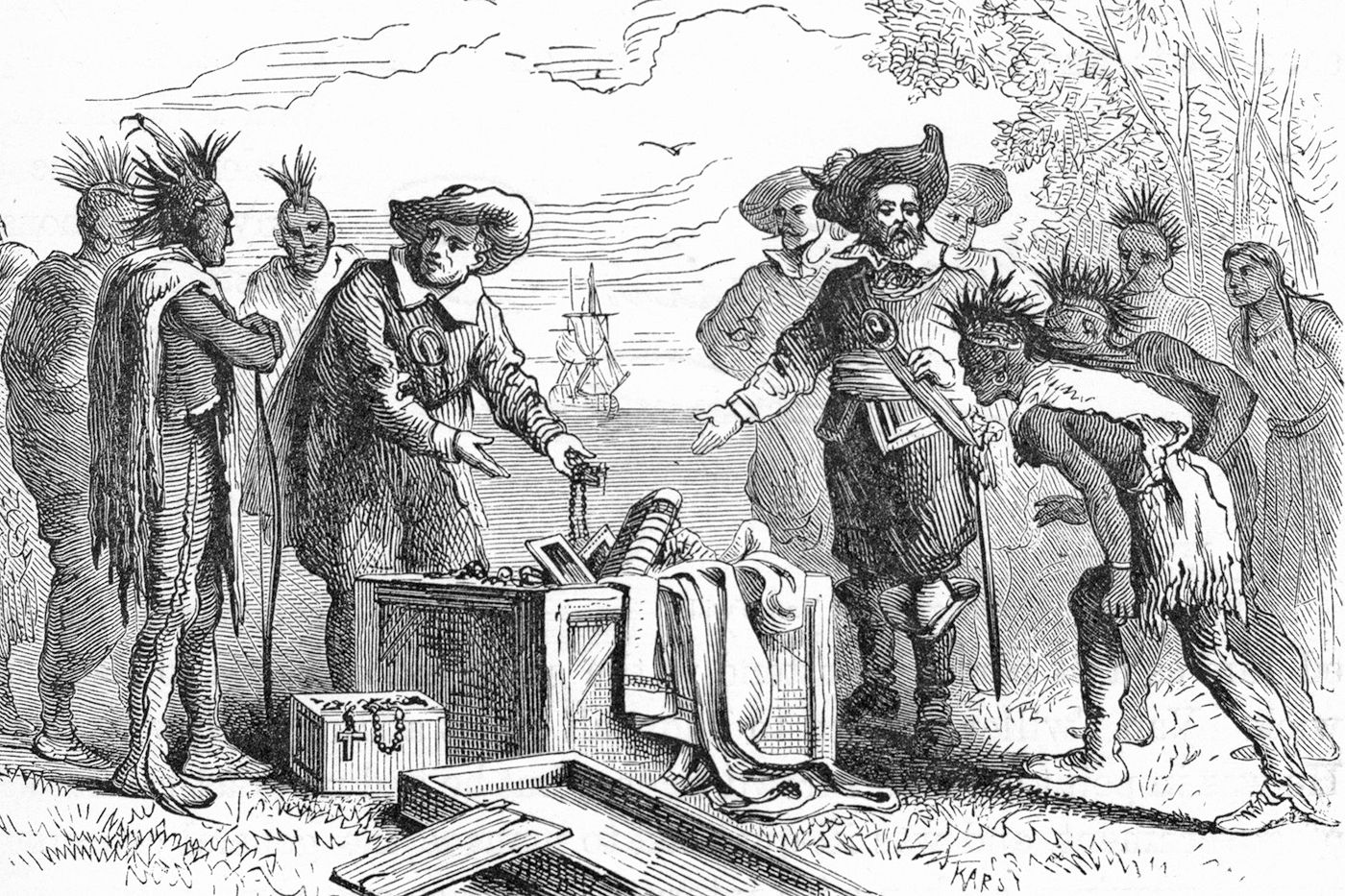

Photo Credit: Alfred Fredericks, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The Beads That Did Not Buy Manhattan Island

Setting History Straight

By Peter Francis, Jr. with Commentary by Crazy Crow

Photo Credit: Alfred Fredericks, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

As history would have you believe, Peter Minuit stepped off a ship from Holland, called the Indians together, and for the paltry sum of $24 worth of beads and assorted gew-gaws purchased the island of Manhattan, closing the “greatest real estate deal in history.”

The story of the purchase of Manhattan is one of the most contentious and oft-disputed stories in American history. That modest sale has gone down in history as the biggest swindle ever perpetrated. The fabled exchange has been dissected and reexamined with the weak hope of proving it a myth. Some people just dismiss the event out of hand, claiming that the infamous exchange never took place at all. The deal seems so unfair, some parties have even suggested that the island be returned to the “original” owners. But what may be the most surprising fact about the whole transaction is that in 1626, and for a long time afterward, both parties were very happy with it. (Raden 2015)

There are many possible reasons for this, but the most obvious is also the simplest: Value is relative. If Minuit had presented the Lenape Indians with a sack full of diamonds, no one would question the merit of the transaction. Because glass beads are even less valuable to us than they were to the Dutch, we assume the Indians got taken. But overabundance always breeds contempt–and if it weren’t for their value on an international scale, locals in Myanmar today might dismiss their own abundant rubies the same way we do glass beads. (Raden 2015)

The majority of this article is made up of a paper by Peter Francis, Jr., “The Beads That Did Not Buy Manhattan Island”. It is a thoroughly researched effort to correct the myth that grew up around this early ‘real estate transaction’ that ultimately sought to show how clever the Europeans were, and how gullible and easily deceived was the ‘ignorant native population’. Read on to learn the truth and, as Paul Harvey would say, “The Rest of the Story!”

We are pleased to present this Peter Francis, Jr. article in its entirety, along with introductory research by Crazy Crow. Peter Francis, Jr. (1945-2002), was a world-renowned bead scholar who was dubbed by the New York Times as the “world’s leading authority on beads.” Read this article, along with The Venetian Bead Story, and we think you’ll know why they titled him so. Document Source: FRANCIS, PETER. “The Beads That Did ‘Not’ Buy Manhattan Island.” New York History 78, no. 4 (1997): 411–28.

Understanding the Roots of Historical Myths: Columbus Proves the World Isn’t Flat (not)

It is similar to the story of Columbus seeking in part to prove with his voyage that the world was not flat (which is a myth). Interestingly, both of these early ‘urban legends’ have to do with Native American history. A brief summary of this story of Columbus is included here to demonstrate how these historical myths originate and are perpetuated, further adding to errors in understanding other events that seemed to flow from them. This summary is excerpted from “Christopher Columbus Never Set Out to Prove the Earth was Round’ by Erin Blakemore, Aug. 31, 2018.

Despite a persistent legend, neither Columbus nor his Spanish patrons thought Earth was a finite plane instead of a round planet. And you can blame one of the United States’ greatest authors for creating a myth that still surrounds one of history’s best-known figures. There’s just one problem: It’s almost certain that in the 1490s, nobody thought the earth was flat. According to historian Jeffrey Burton Russell, “no educated person in the history of Western Civilization from the third century B.C. onward believed that the Earth was flat.”

That was thanks to scientists, philosophers and mathematicians who, as early as around 600 B.C., made observations that Earth was round. Using calculations based on the sun’s rise and fall, shadows and other physical properties of the planet, Greek scholars like Pythagoras and Aristotle determined that the planet is actually a sphere.

The myth of Columbus’ supposed flat earth theory is tempting: It casts the explorer’s intrepid journey in an even more daring light. Problem is, it’s completely untrue. The legend doesn’t even date from Columbus’ own lifetime. Rather, it was invented in 1828, when Washington Irving published The Life and Voyages of Christopher Columbus.

Irving, a master storyteller, was already famous for tales like “Rip Van Winkle” and “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow” when he tackled the life of Columbus. His inspiration came after his friend, Alexander Hill Everett, the United States’ minister to Spain, invited Irving to stay with him in Madrid. While visiting the city, Irving was tempted by a gigantic archive of documents about Columbus and decided to write the explorer’s biography.

The archive may have been extensive, but Irving couldn’t help from adding fictional flourishes to Columbus’ already fascinating life. Crucially, he claimed that when the explorer told Spanish geographers the earth was not actually flat, they refused to believe him, even questioning his faith and endangering his life.

“Is there anyone so foolish, as to believe [in] people who walk with their heels upward, and their head hanging down?” one of the Catholic geographers supposedly exclaimed when Columbus told him the Earth was a circle and not a flat line. When Irving’s book became a runaway bestseller, the supposed confrontation between the rational explorer and the dogmatic official was accepted as truth.

Over the years—and with the help of Antoine-Jean Letronne, a French author—the legend took hold. For years this was taught in American schools (this author can attest to it). Even today, it’s a commonly held belief – yet it couldn’t be further from the truth.

Click to enlarge.

Photo Credit: Alfred Fredericks, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

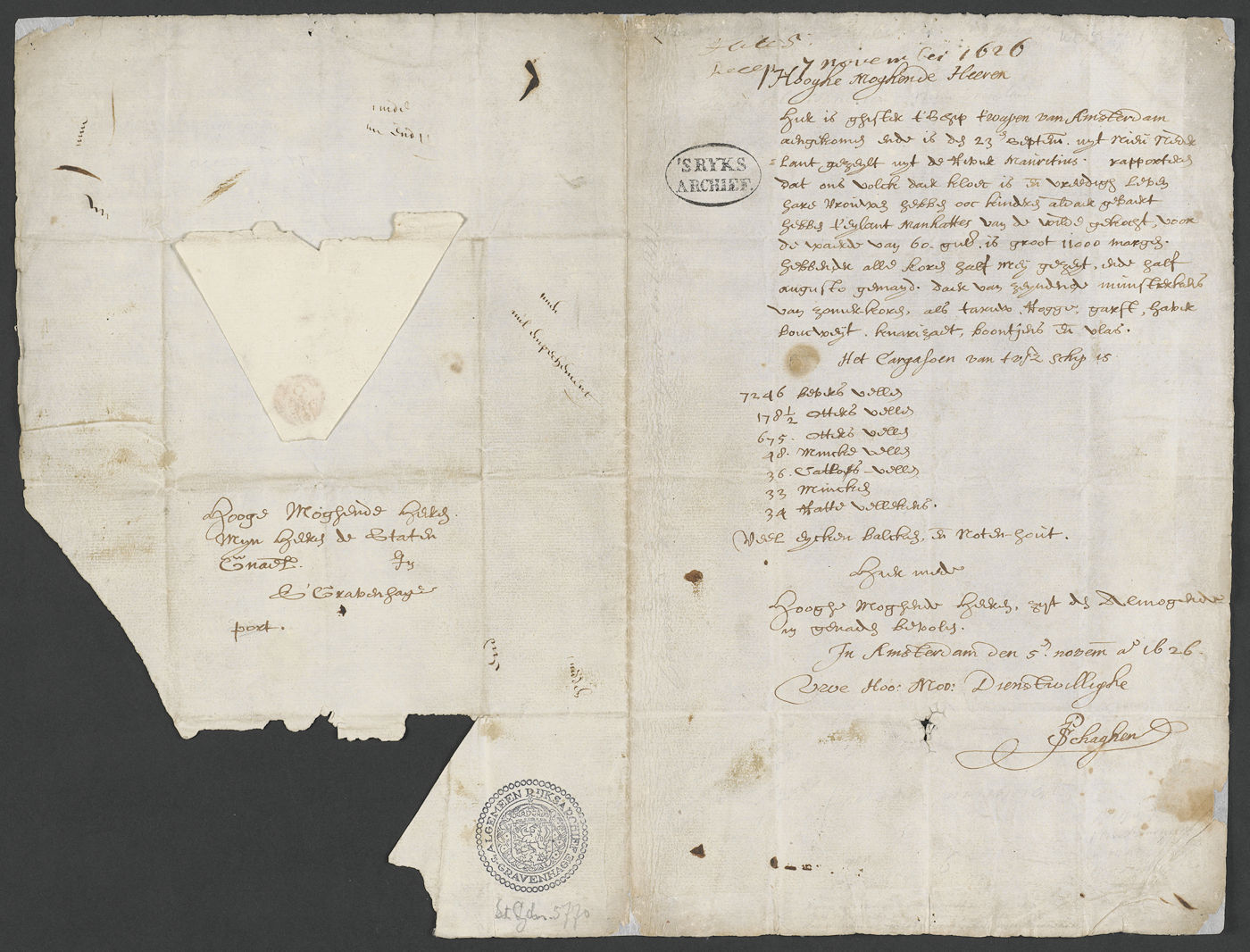

1626 letter in Dutch by Pieter Schaghen stating the purchase of Manhattan for 60 guilders.

A Letter by Pieter Schaghen, board member of the Dutch West India Company, to the States General of the Netherlands. As a council member of the Amsterdam-based West India Company, Schaghen personally represented the federal legislative body of the Dutch Republic, which was seated in The Hague. Schaghen informs his superiors that a ship from New Netherland has arrived in Amsterdam the day before, the 4th of November 1626. This document is part of the collection of the Dutch National Archives in The Hague. Translation [3]: Received (in The Hague): 7th of November 1626. High and mighty lords, The ship ‘The coat of arms of Amsterdam’ has arrived here (in Amsterdam) yesterday and has sailed out of New Netherland on the 23rd of September through the Mauritius River. (Hereby) reporting that our people are in good spirit and are living there peacefully. The women have given birth to children there as well. (They) have bought the Island of Manhattes from the wild man, for the amount of 60 guilders. (The island) measures 11.000 morgen. (They) have sowed all grains in the middle of May and harvested (them) in the middle of August. The samples of summer grain, being wheat, rye, barley, oat, buckwheat, canary grass, beans and flax, are from this (harvest).

The cargo of the aforesaid ship is: 7246 beaver skins 178½ otter skins 675 otter skins (apparently packaged separately from the first shipment of otter skins) 48 mink skins 36 cat skins 33 minks (without further specifications) 34 rat skins Many oak beams and heartwood. Herewith, high and mighty lords, be commended to the mercy of the Almighty. (Written) in Amsterdam, the 5th of November 1626. Your high and mightinesses’ obedient (servant), Pieter Schaghen (signature) Description on the back: High and mighty lords, my lords (of) the States General in The Hague. Next to this diagonally: Without hinderance.

What History Wanted You to Believe

As history would have you believe it, Peter Minuit stepped off the ship from Holland, called the Indians together, and for the paltry sum of twenty-four dollars worth of beads and assorted gew-gaws purchased the island of Manhattan, closing the “greatest real estate deal in history.”

The story of the purchase of Manhattan is one of the most contentious and oft-disputed stories in American history. That modest sale has gone down in history as the biggest swindle ever perpetrated. The fabled exchange has been dissected and reexamined with the weak hope of proving it a myth. Some people just dismiss the event out of hand, claiming it’s apocryphal–that the infamous exchange never took place at all. The deal seems so unfair, some parties have even suggested that the island be returned to the “original” owners. But what may be the most surprising fact about the whole transaction is that in 1626, and for a long time afterward, both parties were very happy with it. (Raden 2015)

There are many possible reasons for this, but the most obvious is also the simplest: Value is relative. If Minuit had presented the Lenape Indians with a sack full of diamonds, no one would question the merit of the transaction. Because glass beads are even less valuable to us than they were to the Dutch, we assume the Indians got taken. But overabundance always breeds contempt–and if it weren’t for their value on an international scale, locals in Myanmar today might dismiss their own abundant rubies the same way we do glass beads. (Raden 2015)

Dispelling the Manhattan Island Purchase Myth

The purchase of Manhattan Island is an unrecorded event dressed in mystery and myth. An examination of the myth and of its history corrects misconceptions that are nearly as ancient as the purchase.

This paper shows that there is no documentary evidence that even suggests that European trade beads were used to buy Manhattan Island. Nonetheless, the association of beads with the Manhattan purchase is commonplace. An enumeration of sources asserting this would be too tedious to list, but a few additional samples can be offered. J.G. Wilson’s Memorial History of the City of New-York (1892) says, “…the glittering beads and baubles and brightly colored cloths filled the minds of the simple Indians with delight” (Wilson 1892, 1:158).

A generation later James Sullivan (1927, 1:157), obviously influenced by Wilson, wrote in his History of New York State, “Glittering beads and baubles, brightly colored cloths, glittering trinkets of small value brought from the ships nearby in chests, and opened on the shore before the eager eyes of the aborigines, were what worked the miracle.”Current New York State school history texts repeat the story. The New Exploring American History by Schwartz and O’Conner (1981:60) says, “Peter Minuit bought the island of Manhattan from the local Indians. Minuit paid $24 worth of colored beads and trinkets for the island.”

Click to enlarge.

Photo Credit: FRANCIS, PETER. The Beads That Did ‘Not’ Buy Manhattan Island.” New York History 78, no. 4 (1997): 411–28.

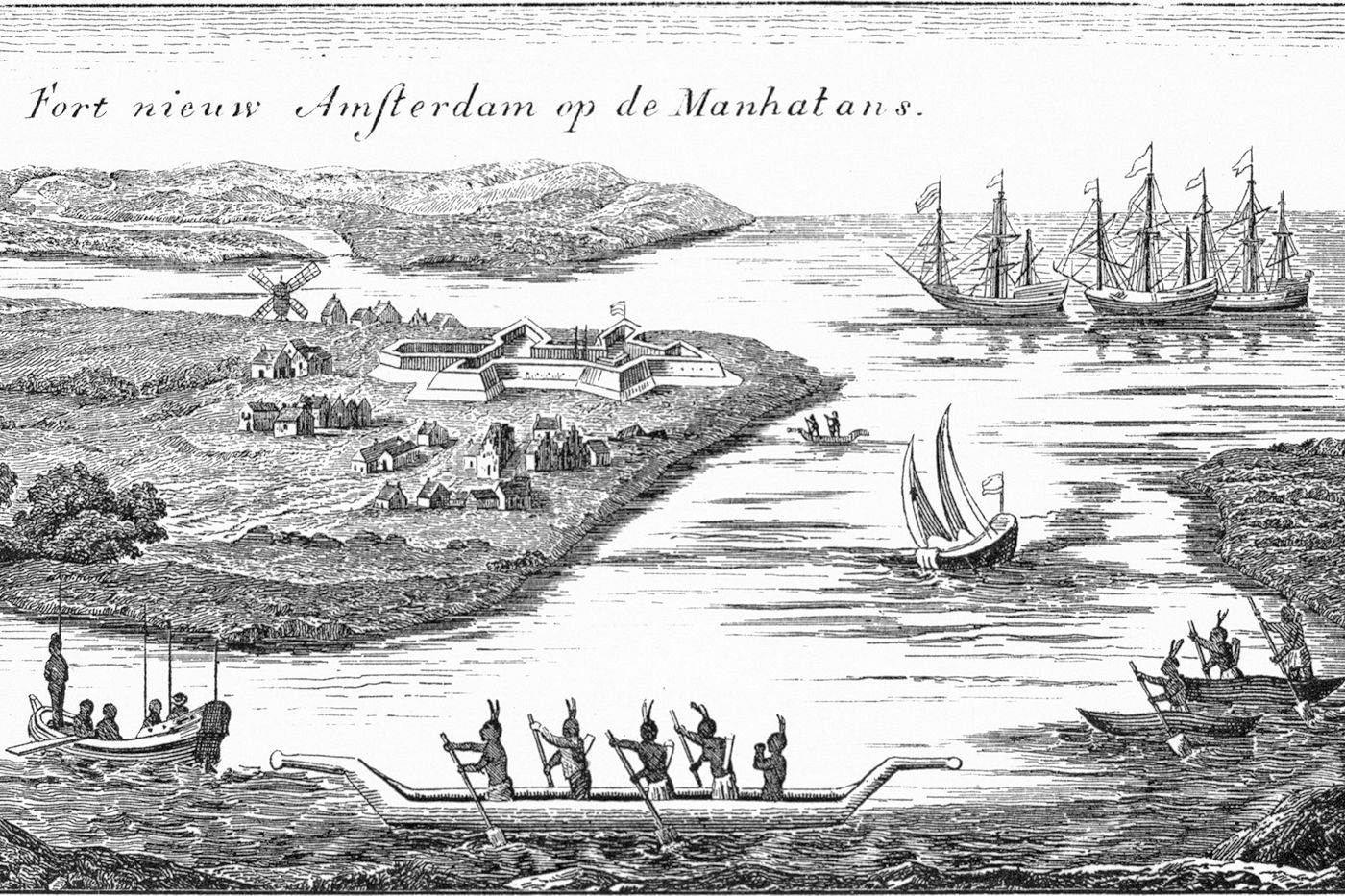

The Dutch settlement on Manhattan, drawn by a Dutch officer in 1635 (Lamb 1877, 1:77). The Beads That Did Not Buy Manhattan Island by Peter Francis.

Click to enlarge.

Photo Credit: FRANCIS, PETER. The Beads That Did ‘Not’ Buy Manhattan Island.” New York History 78, no. 4 (1997): 411–28.

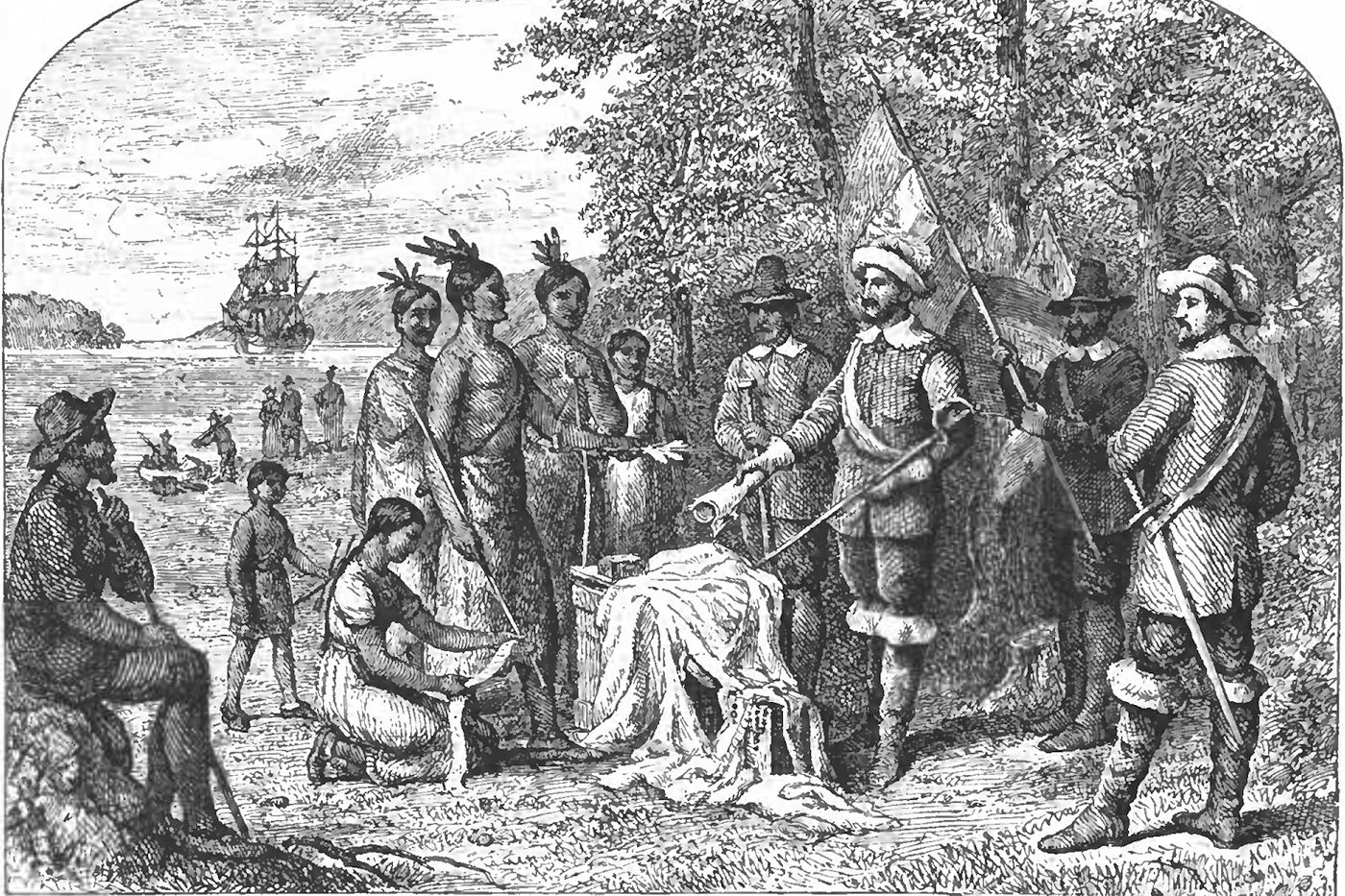

Depiction of the purchase of Manhattan Island from Wilson (1892, 1:152). The Beads That Did Not Buy Manhattan Island by Peter Francis.

And, of course, those interested in beads, such as Erikson (1969:22) in her The Universal Bead, share in the myth: “…and included in the barter for Manhattan, as we have all been taught, were strings of glass beads.”

And so have all Americans been taught. But where did the story originate? Certainly not from the available evidence.

One of the earliest histories of New York was William Smith, Jr.’s History of the Province of New York, published in 1757. Smith mentions neither beads nor anything else used to buy Manhattan because the purchase was not known to him. Washington Irving’s (1809) Diedrich Knickerbocker’s A History of New-York, based largely on Smith and the source of many early New York myths, also makes no mention of any purchase. The first historian to write about the purchase of Manhattan was N.C. Lambrechtsen, whose A History of the New Netherlands states that Pavonia and Hoboken (both in New Jersey), Nut Island, Staten Island, and Manhattan Island were all bought from the Indians. Lambrechtsen must have studied the Dutch archives; the work appeared in Dutch in 1818 and was translated into English in 184l (Kemp 1841:91). His work, however, had no affect upon American historians.

Joseph W. Moulton’s Novum Belgium (1826) was the first American history to say that Manhattan had been bought from the Indians. This account, however, was completely fictitious, describing how small tracts were bought one at a time on lower Manhattan (Moulton 1826:427). It is difficult to discern what his sources may have been; a contemporary historian, George Folsom (1841:450), asserted that Moul- ton’s only source was his own fertile imagination.

Click to enlarge.

Photo Credit: FRANCIS, PETER. The Beads That Did ‘Not’ Buy Manhattan Island.” New York History 78, no. 4 (1997): 411–28.

The Dutch settlement on Manhattan, drawn by a Dutch officer in 1635 (Lamb 1877, 1:77). The Beads That Did Not Buy Manhattan Island by Peter Francis.

Click to enlarge.

Photo Credit: FRANCIS, PETER. The Beads That Did ‘Not’ Buy Manhattan Island.” New York History 78, no. 4 (1997): 411–28.

Wampum recovered from the Seneca Power House site (ca. 1635-1655) in western New York State (courtesy: George Hamell). The Beads That Did Not Buy Manhattan Island by Peter Francis.

INTRODUCTION

One of the best known and most widely quoted events of early American history is the story of the Dutch purchase of Manhattan Island from its aboriginal proprietors. The incident is often depicted in cartoons, on television, and in other forms of popular media. Nearly all Americans know the simple elements of this tale: Peter Minuit arrived as director-general of New Netherland in 1626, and soon set about buying Manhattan from the natives with twenty-four dollars worth of beads and similar goods. Its outline has been essentially unchanged in histories and text books for generations: One of the first acts of Director Minuet was to purchase Manhattan Island for twenty-four dollars, at the rate of one cent for ten acres, paid in gay clothing, beads, and brass ornaments (Hendrick 1896:18). The first important act of Minuit’s administration was the purchase of the island of Manhattan from the natives…. From these Indians Minuit bought the whole island, containing about 22,000 acres, for the value of 60 guilders in beads and ribbons…. That must have furnished enough ribbons and beads to give every brave and every squaw a chance [at having some] (Fiske 1899, 1:120).

The famous purchase of Manhattan Island for sixty guilders, or about twenty-four dollars, was by order of the directors in Holland, in their instructions to Verhulst. The money was paid in the usual form of trading goods, knives, beads and trinkets (Andrews 1937, 1:74, n. 30).

He [Minuit] arranged the purchase of Manhattan Island from the Indians. The price of the famous sale was 60 guilders or 24 dollars’ worth of beads and other trinkets (Tyrrell 1963:48).

The transaction is often treated lightly. The thought of one of the world’s most valuable tracts of land traded for mere beads tickles the modern funny bone. But this is a misreading of history. Although early explorers did refer to beads as “trinkets,” “toys,” and even “trash,” modern historians should be aware of the role beads played in the settlement of America and their value to the natives. No one has seriously considered the goods used to purchase Manhattan nor attempted to learn more about the beads themselves. Yet it is a matter of importance.

GLASS BEADS IN THE EARLY TRADE

Glass beads played a minor but constant role in the European global exploration beginning in the 15th century. At his first American landfall, Christopher Columbus reported in his journal for 12 October 1492 that he gave away red caps and strings of beads; the natives immediately put the beads around their necks. Following Columbus there were hardly any explorers or settlers coming to America who did not carry beads to give or barter; their journals are replete with references to them (Francis 1984:24-27; Morison 1963:64-65).

The use of European glass trade beads was well established by the time the Dutch were exploring and settling their colony of New Netherland (Figure 1). The leading glass beadmaker of Europe was Venice, Italy, whose beads traveled to all inhabited continents, and were an essential trade item in world commerce for centuries. Other European nations developed rival glass bead industries, including the Netherlands, which had a flourishing beadmaking industry of its own throughout the 17th century (Francis 1979:6; Karklins 1974:64-82; Sleen 1962).

European trade beads were as important to the Dutch in their American colonies as to anyone anywhere. When the Englishman, Henry Hudson, sailed for the Netherlands in 1609, he met natives along the Maine coast who told

e Dutch settlement on Manhattan, drawn by a Dutch officer in 1635 (Lamb 1877, 1:77).

him that they were trading furs to the French for cloth, knives, hatchets, kettles, and other goods, including beads. In New York harbor, Hudson gave away knives and beads in exchange for some green tobacco. Up the “Great River,” which was later named for Hudson, near the present site of Albany, something of a twist occurred when the natives presented him with beads (Purchas 1626, 8:586-594). These were doubtless wampum beads, the highly valued shell beads, which we shall meet later.

Once the New Netherland colony had been established, glass beads figured prominently in the economy of the settlement. The secretary of the colony, Issack de Rasiere, who arrived on 28 July 1626, learned the value of glass beads quickly. In his letter to the Amsterdam Chamber of the West India Company on 23 September of that year, he mentioned the importance of glass beads several times. He had bought ten beaver skins from the Minquac Indians for some cloth, two hatchets, a small quantity of beads (“een deel corael”), and some other items. A bunch of beads, strung in hanks, which was a common method of transporting them, figured in the trade between Jacob Jopaz and Pieter Barentsz in which the former had traded European goods for 205 beaver pelts and some wampum (Laer 1924:192, 220).

Along with his letter, de Rasiere sent two strings of beads, one black and one white, to the West India Company as samples, and asked them to send him two or three hundred pounds of similar beads, “as these are much sought after and there are no more here.” He also explained that he had sold the colonists ten to twenty pounds of beads directly because they could use them to trade with the Indians for fresh food, “because they complain so much of the victuals” (Laer 1924:132).

The primary use for these glass beads was decorative. The natives valued them for their ornamental purposes and wore them as jewelry. Trade beads quickly became an integral part of native costume. De Rasiere explained in a letter of 1628 to his friend, Samuel Blommaert, that the Indians used their own wampum as a bride price, and that after the price had been decided upon, the suitor gave his intended, “all the Dutch beads he has, which they call Machampe” (Jameson 1909:107).

In short, there is no question about the importance of glass trade beads in the early exploration of America in general nor to the New Netherland settlement in particular. It remains, however, to examine the details surrounding

the purchase of Manhattan Island to determine what sorts of beads were used in the transaction and where they may have been made, whether in Venice, the Netherlands, or elsewhere.

THE DUTCH ACQUISITION OF MANHATTAN

Following Hudson’s voyage of 1609, a number of Dutch ships sailed into New York harbor and up the Hudson River to establish temporary fur trading posts. Though the Dutch considered this area of less importance than their holdings in either Brazil or the West Indies, it was included among the responsibilities of the Dutch West India Company, which was organized in 1621. The management of the West India Company was jointly shared by the Dutch parliament, the States-General, and the directors of the company, called “the Nineteen.”

The first group of settlers to New Netherland sailed from Amsterdam in March of 1624 with Cornelius May as the captain and first director of the colony. The Nineteen issued a set of instructions to the colonists, which included the orders that they should take special care in their dealings with the Indians. They were admonished to be faithful in their contracts with the natives, and not to “give them any offense with cause as regards their persons, wives or property” (Laer 1924:17). The first colonists settled at three locations: Fort Orange, on the site of modern Albany; Noten or Nut Island, now Governor’s Island, in New York harbor; and at High Island, identified with Burlington Island in the Delaware River, south of Trenton, New Jersey (Weslager 1968:6).

In January of the following year (1625), the Orange Tree left Amsterdam bound for New Netherland with more colonists. Among them was William Verhulst (also spelled van Hulst), who had been appointed as the second director of the colony. Verhulst had been given written instructions from the West India Company, including a directive about how to deal with claims to the land:

Click to enlarge.

Photo Credit: English Wikipedia, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Peter Minuit portrait New Amsterdam 1600s.

Click to enlarge.

Photo Credit: Samuel Blommaert in 1647 by an unknown artist, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Portrait of Samuel Blommaert (1583-1654) – 1622 director West India Company in 1622.

Also arriving on the Orange Tree with Verhulst was Peter Minuit. Born of French Protestant parents in Wesel, Germany in 1590, Minuit was, like many explorers of his day, a mercenary. After he worked for the Dutch he became the director of New Sweden (Delaware). Minuit’s assignments in New Netherland were spelled out by the West India Company to Verhulst, who was charged with having Minuit sail up the Hudson and explore the territory, to dig for valuable minerals, and to identify useful products of the region (Laer 1924:49, 75).

The three areas that the Dutch originally settled were found not to be entirely satisfactory. Fort Orange eventually survived, but in its first year had experienced floods. High Island was abandoned, and Nut Island was found to be too small for pasturage. On 22 April 1625, the West India Company sent out Further Instructions to Verhulst to find a better location for the settlement, as well as instructions to Cryn Fredericksz to lay out a fort to be named Amsterdam (Laer 1924:82-129, 132-169). Included in the Further Instructions for Verhulst was a more specific directive about obtaining land:

After the Further Instructions of 22 April 1625, there are no known documents concerning New Netherland for over a year. A letter written by Minuit to Barentsz on 11 May 1626 revealed his intentions to buy Manhattan in the near future (Gehring 1980:6-7). The next evidence which has survived are three documents associated with the passage of the Arms of Amsterdam, which sailed from New Netherland on 23 September 1626, and arrived at Amsterdam on 4 November. All of these three were written after the purchase.

One of these is the letter of de Rasiere, to which we have already referred, written on 23 September 1626, the day the ship left the colony. De Rasiere made no mention of the Manhattan purchase, which he surely would have done had it been affected while he was in New Netherland; the purchase must have taken place before his arrival on 28 July 1626.

The second document is the only contemporary evidence for the purchase of Manhattan, and allows us to place the date of the purchase back a bit further. It is a letter written by Peter Schagen, a member of the Nineteen of the West India Company, to the States-General on 5 November 1626, which recounts the news he had gathered from the crew and passengers on the Arms of Amsterdam after it arrived. It says in part:

The third piece of evidence is the description of the colony which Nicolaes Wassenaer gathered from the people on the Arms of Amsterdam and used for his Historisch Verhael. He reported that the plans for the fort had been laid out, a sawmill and a windmill had been built, and New Amsterdam was a bustling community (Jameson 1909: 83-86). The date of 22 April 1625, when the Further Instructions were written, has been accepted by the City of New York as the official date for its founding. A City Council resolution of 8 January 1975 proclaimed 1975 to be the 350th anniversary of the city, owing largely to the efforts of the Holland Society. The date of the city’s founding on its seal and flag, which until that time had been 1664, the year when the English took over from the Dutch, was also changed to 1625 (Zabriskie and Kenney 1977a:11-14).

The date and circumstances of the purchase of Manhattan are not fully revealed by the surviving evidence. Some historians had believed that Minuit was not director- general of the colony when it was bought and that it was purchased while William Verhulst was in charge, although Minuit or Adrien Theinpont may have negotiated the contract (Zabriskie and Kenney 1977b:12). Verhulst was sent home in disgrace on the Arms of Amsterdam because of his inconsistent, poor administration (Laer 1924:176). However, documents recently uncovered in the New York State Library at Albany by Charles Gehring, including the letter to Barentsz from Minuit, show that Minuit was director-general of the colony when Manhattan was bought and that the purchase was probably made shortly after 11 May 1626, so that the grain could be sown by mid May as Schagen reported to the Nineteen.

The basic documents for the study of New Netherland were discovered by Harmanus Bleeker, an Albany Dutch- man, who served as the ambassador to the Netherlands under Martin Van Buren, himself a New Yorker of Dutch descent. In 1839, Bleeker persuaded the New York legislature to send his secretary, John R. Brodhead, to Amsterdam to transcribe materials in the state archives. Three years later Brodhead returned with a rich harvest of papers which were translated and edited by E.B. O’Callaghan and published in Documents Relative to the Colonial History of the State of New York, under the authority of another act of the state legislature.

Brodhead knew that some material had been removed from the Dutch archives and sold as waste paper and was presumed lost to historians. In 1910, however, six documents written between 1624 and 1626 were offered at auction, including the instructions to May, the Further Instructions to Verhulst, the de Rasiere letter of 1626, and the letter to Cryn Fredericksz about building Fort Amsterdam. They were bought by Henry Huntington, translated by A.J.F. van Laer, and published in California in 1924. These Van Rappard Documents, as they are commonly called, are a valuable supplement to the papers Brodhead transcribed.

As we have seen, the documentary evidence for the purchase of Manhattan is extremely scanty. No deed has survived, although the West India Company specifically instructed that a deed be secured. Unless the deed for Manhattan surfaces sometime in the future, an unlikely though not impossible event, we shall never know the terms of purchase beyond the fact that the Dutch valued its worth at sixty guilders. However, some idea of what may have been used for the purchase of Manhattan can be gathered from the record of the purchase of Staten Island.

BEADS IN THE PURCHASE OF MANHATTAN

The original deed to Staten Island has not survived either, but before it was lost a copy was made by Cornelius Melyen. It shows that Minuit and five other colonists bought the island on 10 August 1626. The natives, who were represented by seven named leaders, received for the island, “Some Diffies [duffles; that is, cloth], Kittles [kettles], Axes, Hoes, Wampum, Drilling Awls, Jews Harps, and diverse other wares, which were all particularized” (The Melyen Papers” 1913:124)(Figures 2-3).

These objects may seem of little worth to us, especially compared to real estate, but to the natives, who had no concept of the possession of land, they were of great value. Cloth and metal items were scarce and novel and, especially in the case of kettles, hoes, and axes, were generally superior to their own equipment. Jews harps are not really necessary items, but even small musical instruments were no doubt greatly admired. Drilling awls can be used for a number of tasks, but of the uses to which they may be put, the manufacture of wampum was probably foremost. The natives of New York harbor and southern New England were the producers of this highly prized bead (Figure 4). The ease of drilling shell with European metal drills rather than with stone implements was an important factor in the growth of wampum manufacturing and trade.

It is important to note here that no glass trade beads are named in Melyen’s abbreviated copy of the Staten Island deed. They may have been included in his “other wares” category. But even if they had been, they were clearly not an important component of the purchase price.

The beads which are mentioned in the Staten Island deed are the native-made wampum beads of shell. It is impossible to overstate the importance of wampum to the Indians and European colonists during this period of American history. The Dutch recognized the value of these small shell beads so well that a string of wampum encircling a beaver was used on the official seal of New Netherland.

The juxtaposition of the beaver and the wampum string was most appropriate. The Dutch were geographically positioned so that they could easily gain control of the wampum trade, as the Indians of eastern Long Island and Narragansett Bay were the main producers. This they sought to do early because wampum could be traded inland for pelts which would yield a 900 percent profit in Europe.2 Soon after his arrival, de Rasiere recognized the value of wampum. His letter of 23 September 1626, informed the West India Company:

De Rasiere also introduced wampum to the Plymouth settlers in 1628. They soon recognized its value so well that the first Euro-Indian war, the Pequot War of 1637, was waged largely over who would control the wampum trade. Wampum became currency throughout the colonies, and was still legal tender in New York as late as 1701 (Bradford 1966:203; Fernow 1893, 4:299; Josephy 1982:32-75).

It is, however, doubtful that the Indians regarded the wampum given to them for Staten Island as payment in the sense of currency. The monetary use of wampum was a European invention, necessitated by the acute coin shortage of the colonies. The Indians were more likely to have regarded the wampum as a sign of agreement. The use of wampum to ratify treaties and other compacts was an Indian conception, and not appreciated by the Europeans until some time later.3 Lending support to this supposition was the inclusion of drilling awls in the Staten Island purchase price, most probably used primarily to make more wampum.

THE BEAD MYTH

The foregoing shows that there is no documentary evidence that even suggests that European trade beads were used to buy Manhattan Island. Nonetheless, the association of beads with the Manhattan purchase is commonplace. An enumeration of sources asserting this would be too tedious to list, but a few additional samples can be offered. J.G. Wilson’s Memorial History of the City of New-York (1892) says, “…the glittering beads and baubles and brightly colored cloths filled the minds of the simple Indians with delight” (Wilson 1892, 1:158).

A generation later James Sullivan (1927, 1:157), obviously influenced by Wilson, wrote in his History of New York State, “Glittering beads and baubles, brightly colored cloths, glittering trinkets of small value brought from the ships nearby in chests, and opened on the shore before the eager eyes of the aborigines, were what worked the miracle.”

Current New York State school history texts repeat the story. The New Exploring American History by Schwartz and O’Conner (1981:60) says, “Peter Minuit bought the island of Manhattan from the local Indians. Minuit paid $24 worth of colored beads and trinkets for the island.”

And, of course, those interested in beads, such as Erikson (1969:22) in her The Universal Bead, share in the myth: “…and included in the barter for Manhattan, as we have all been taught, were strings of glass beads.”

And so have all Americans been taught. But where did the story originate? Certainly not from the available evidence. One of the earliest histories of New York was William Smith, Jr.’s History of the Province of New York, published in 1757. Smith mentions neither beads nor anything else used to buy Manhattan because the purchase was not known to him. Washington Irving’s (1809) Diedrich Knickerbocker’s A History of New-York, based largely on Smith and the source of many early New York myths, also makes no mention of any purchase. The first historian to write about the purchase of Manhattan was N.C. Lambrechtsen, whose A History of the New Netherlands states that Pavonia and Hoboken (both in New Jersey), Nut Island, Staten Island, and Manhattan Island were all bought from the Indians. Lambrechtsen must have studied the Dutch archives; the work appeared in Dutch in 1818 and was translated into English in 184l (Kemp 1841:91). His work, however, had no affect upon American historians.

Joseph W. Moulton’s Novum Belgium (1826) was the first American history to say that Manhattan had been bought from the Indians. This account, however, was completely fictitious, describing how small tracts were bought one at a time on lower Manhattan (Moulton 1826:427). It is difficult to discern what his sources may have been; a contemporary historian, George Folsom (1841:450), asserted that Moul- ton’s only source was his own fertile imagination.

During the following two decades a number of histories of New York appeared, including Macauley’s The Natural, Statistical, and Civil History of the State of New-York (1829), Eastman’s A History of the State of New York (1832), Dunlap’s History of the New Netherlands, Province of New York and State of New York (1839), Barber and Howe’s Historical Collections of the State of New York (1842), and Watson’s Annals and Occurences of New York City and State in Olden Time (1846). None of them mention the purchase of Manhattan.

Only after Brodhead had returned from Amsterdam with the material from the Dutch archives that he had so tirelessly tracked down, was the purchase discussed again. O’Callaghan’s History of New Netherlands, published in 1846, says: “The island of Manhattans, estimated then to contain twenty-two thousand acres of land, was therefore purchased from the Indians, who received for that splendid tract the trifling sum of sixty guilders or twenty-four dollars” (O’Callaghan 1846, 1:104). His source was the Peter Schagen letter of 5 November 1626, which gives the purchase price only as “the value of 60 guilders.”

At this point it is interesting to note how old the figure of twenty-four dollars is in regard to this purchase. Recent historians who have traced the historiography of the Manhattan purchase have suggested that the figure was first used by Anderson and Flick in 1902 or by Riker in 1881 (Weslager 1968:5; Zabriskie and Kenney 1977a:11). It is clearly much older than that. During the next three decades the purchase of Man- hattan Island for twenty-four dollars equaling sixty guilders is repeated by virtually every historian and textbook writer dealing with the history of New York. Among them were: Mather in A Geographical History of the State of New York (1848), Brodhead in History of the State of New York (1853), Valentine in History of the City of New York (1853), Vogelvanger in “The Manhattan Papers” which appeared in The Sunday Times4 (1859-1860), Booth in History of the City of New York (1867), Randall in History of the State of New York (1870), and Stone in History of New York City (1872).

Randall appears to have been the first writer to have pointed out that the purchase would not have been made in coin. He suggested that trinkets and other goods would have been used instead (Randall 1870:19). With this there is no argument. The error that has been made was in trying to enumerate and identify, without any proof, the trading goods that were used, and presenting this identification as fact.

Beads were first brought into the picture in 1877 by Martha J. Lamb in her History of the City of New York. As far as can be determined by the present survey of historical works, this is the first attempt to list the actual goods exchanged for Manhattan, but the list is only a product of the author’s imagination. She wrote: “He [Minuit] then called together some of the principal Indian chiefs, and offered beads, buttons, and other trinkets in exchange for their real estate. They accepted the terms with unfeigned delight, and the bargain was closed at once” (Lamb 1877, 1:53). Now the myth was complete. Peter Minuit stepped off the ship from Holland, called the Indians together, and for the paltry sum of twenty-four dollars worth of beads and assorted gew-gaws purchased the island of Manhattan, closing the “greatest real estate deal in history.”

The story has been so often repeated and so widely illustrated, particularly by Alfred Frederick’s painting, commissioned by the Title Guarantee and Trust Company, that it has become firmly rooted in American folklore. Nearly all laymen and most (although not all) professional historians have taken it for fact.

Some writers have been concerned about the equating of sixty guilders of the 1620s with the modern twenty-four dollars. O’Callaghan was clearly thinking of gold coin, and his estimate was par for his day. Others have not been happy with the figure. George W. Schuyler (1885:11, n. l) estimated that in that year it was worth three hundred dollars. John Fiske (1899, 1:121) estimated its worth at one hundred and twenty dollars. Morison (1965:57) suggested a value of only forty dollars, apparently reflecting a bit more than an ounce of gold, now much elevated in price.

The most interesting calculation of the value of the purchase of Manhattan was made by John J. Anderson and Alexander C. Flick in A Short History of the State of New York (1901), when they reckoned that if the twenty-four dollars had been put at 6 percent compound interest it would be worth $122,500,000 by the time they were writing. They must have calculated the amount from 1626 to 1891; by the time their book appeared in 1902 it would have been worth over 231 million dollars. In the same spirit, if we make a similar calculation from 1626 to 1986, we arrive at a figure of

nearly 31 billion dollars! Viewed in this way, the purchase of underdeveloped land was not too unfair, if only the Canarsie Indians had had access to a bank account.

James Wilson was so concerned about the price for Manhattan that in 1875 he asked the Queen of the Netherlands (Sophia) if she thought it had been unfair. Her Majesty’s reply was that it had been perfectly fair because: “If the savages had received more for their land they would simply have drunk more fire-water. With sixty florins [guilders] they could not purchase sufficient to intoxicate each member of the tribe!” (Wilson 1892, 1:158). Her majesty obviously envisioned payment in coin and a neighborhood bar. Daniel Van Pelt thought her comments unamusing, not because of the racial slur, but because he believed the price equitable on other grounds:

The foregoing shows that there is no documentary evidence that even suggests that European trade beads were used to buy Manhattan Island. Nonetheless, the association of beads with the Manhattan purchase is commonplace. An enumeration of sources asserting this would be too tedious to list, but a few additional samples can be offered. J.G. Wilson’s Memorial History of the City of New-York (1892) says, “…the glittering beads and baubles and brightly colored cloths filled the minds of the simple Indians with delight” (Wilson 1892, 1:158).

A generation later James Sullivan (1927, 1:157), obviously influenced by Wilson, wrote in his History of New York State, “Glittering beads and baubles, brightly colored cloths, glittering trinkets of small value brought from the ships nearby in chests, and opened on the shore before the eager eyes of the aborigines, were what worked the miracle.”

Current New York State school history texts repeat the story. The New Exploring American History by Schwartz and O’Conner (1981:60) says, “Peter Minuit bought the island of Manhattan from the local Indians. Minuit paid $24 worth of colored beads and trinkets for the island.”

And, of course, those interested in beads, such as Erikson (1969:22) in her The Universal Bead, share in the myth: “…and included in the barter for Manhattan, as we have all been taught, were strings of glass beads.”

And so have all Americans been taught. But where did the story originate? Certainly not from the available evidence. One of the earliest histories of New York was William Smith, Jr.’s History of the Province of New York, published in 1757. Smith mentions neither beads nor anything else used to buy Manhattan because the purchase was not known to him. Washington Irving’s (1809) Diedrich Knickerbocker’s A History of New-York, based largely on Smith and the source of many early New York myths, also makes no mention of any purchase. The first historian to write about the purchase of Manhattan was N.C. Lambrechtsen, whose A History of the New Netherlands states that Pavonia and Hoboken (both in New Jersey), Nut Island, Staten Island, and Manhattan Island were all bought from the Indians. Lambrechtsen must have studied the Dutch archives; the work appeared in Dutch in 1818 and was translated into English in 184l (Kemp 1841:91). His work, however, had no affect upon American historians.

Joseph W. Moulton’s Novum Belgium (1826) was the first American history to say that Manhattan had been bought from the Indians. This account, however, was completely fictitious, describing how small tracts were bought one at a time on lower Manhattan (Moulton 1826:427). It is difficult to discern what his sources may have been; a contemporary historian, George Folsom (1841:450), asserted that Moul- ton’s only source was his own fertile imagination.

During the following two decades a number of histories of New York appeared, including Macauley’s The Natural, Statistical, and Civil History of the State of New-York (1829), Eastman’s A History of the State of New York (1832), Dunlap’s History of the New Netherlands, Province of New York and State of New York (1839), Barber and Howe’s Historical Collections of the State of New York (1842), and Watson’s Annals and Occurences of New York City and State in Olden Time (1846). None of them mention the purchase of Manhattan.

After all this, it seems a shame not to have the Indians’ side of the story of first meeting the Dutch on Manhattan. Or do we? One of the most fascinating documents of early New York history was gathered by the Rev. John Heckewelder about 1760 from the elders of the tribes who once lived around New York harbor: The Indians said they saw a ship (apparently Hudson’s Half Moon) approaching the island, and they dressed up believing it to be their spirit Mannitto. When the Dutch landed, they drank with the Indians and gave them “beads, axes, hoes, stockings &c” and said that they would return in a year and “should then want a little land of them to sow some seeds in order to raise herbs to put in their broth” (Collections of the New-York Historical Society 1841:69-74; Heckewelder 1876:71-75).

The next year (if this account is true, it would have been two years later when Hendrick Christiansen returned in 1611) the Dutch found that the Indians were wearing the hoes and axes around their necks like pendants and using the stockings for tobacco pouches. The Dutch put handles on the tools and showed the Indians how to use them and how to wear the stockings. “Here (they say) a general laughter ensued among them (the Indians) that they remained for so long a time ignorant of the use of so valuable implements; and had borne with the weight of such heavy metal hanging

to their necks for such a long time” (Heckewelder 1841:73). The Indians retained their good humor when the Dutch asked for land that a hide would cover or encompass, and then proceeded to cut a hide spirally into a long thin thong which enclosed a large plot of land when unrolled. The account ended with these words:

All the tribal elders told Heckewelder a similar story, and one of them said that he had heard it from his grandfather fifty years before (Yates 1824:229). The account may therefore be only two or three generations removed from the actual events. Though some later historians have doubted the validity of this tale (Goodwin 1919:10; Hamilton 1959:23), pre-literate people are often surprisingly accurate when transmitting their own cultural history. The account may be more factual than has been assumed, and though it does not document the purchase of Manhattan, it does tell us how the Indians accounted for the Dutch gaining control of the island.

The tradition at least sounds authentic. The Indians could easily laugh at themselves for wearing the heavy tools as well as at the Dutch trick of getting a large plot of land with a single hide. The last sentence of the account (the Dutch “asked from time to time…”) even sounds as though it had been added clause by clause as the newcomers came to dominate an increasing amount of land. In any case, it certainly demonstrates the native love for beads and other sorts of personal adornments, and it sets the stage for later developments.

CONCLUSION

It is difficult to judge the authenticity of the story Heckewelder reported. Nonetheless, it is at least as good as the old myth we others have long believed about a wily Dutchman buying the heart of America’s greatest city for a couple of handfuls of beads worth a few dollars.

END NOTES

REFERENCES CITED

- 1

- 2Anderson, John J. and Alexander C. Flick- 1901 A Short History of the State of New York. Maynard, Merrill, New York.

- 3Andrews, C.M.- 1937 The Colonial Period of American History: The Settlements. Yale University Press, New Haven.

- 4Barber, John W. and Henry Howe- 1842 Historical Collections of the State of New York. Tuttle, New York.

- 5Booth, Mary L.- 1867 History of the City of New York. W.R.C. Clark, New York.

- 6Bradford, William- 1966 Of Plymouth Plantation, 1620-1647, edited by S.E. Morison. New York.

- 7Brodhead, John R.- 1853 History of the State of New York. Harper, New York.

- 8Bunce, James E. and Richard P. Harmond (eds.)- 1977 Long Island as America: A Documentary History to 1896. Kennikat Press, Port Washington, NY.

- 9Dunlap, William- 1839 History of the New Netherlands, Province of New York, and State of New York. Carter & Thorp, New York.

- 10Eastman, Francis S.- 1832 A History of the State of New York. A.K. White, New York.

- 11Erikson, Joan M.- 1969 The Universal Bead. Norton, New York.

- 12Fernow, Bertold- 1893 Coins and Currency in New-York. In The Memorial History of the City of New York, by James G. Wilson. New York.

- 13Fiske, John- 1899 The Dutch and Quaker Colonies in America. Houghton, Mifflin, Boston.

- 14Folsom, George- 1841 A Few Particulars Concerning the Directors General or Governors of New Netherlands. Collections of the New- York Historical Society, 2nd series. New York.

- 15Francis, Peter, Jr.- 1979 The Story of Venetian Beads. World of Beads Monograph Series 1. Lake Placid, NY; 1984 Bead Report XII: Beads and the Discovery of America. Part II: Beads Brought to America. Ornament 8(2):24-27.

- 16Gehring, Charles- 1980 Peter Minuit’s Purchase of Manhattan Island – New Evidence. De Halve Maen 54.

- 17Goodwin, Maud Wilder- 1919 Dutch and English on the Hudson. Chronicles of America Series. Yale University Press, New Haven.

- 18Hamilton, Milton W.- 1959 Henry Hudson and the Dutch in New York. University of the State of New York, Albany.

- 19Heckewelder, John- 1819 History, Manners, and Customs of the Indian Nations Who Once Inhabited Pennsylvania and the Neighbouring States, edited by William C. Reichel. Reprinted in 1876 by The Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.; 1841 Indian Tradition of the First Arrival of the Dutch at Manhattan Island, now New-York. Collections of the New- York Historical Society, 2nd series. New York.

- 20Hendrick, Welland- 1896 A Brief History of the Empire State for Schools and Families. C.W. Bardeen, Syracuse.

- 21Irving, Washington- 1809 A History of New York, by Diedrich Knickerbocker. Inskeep & Bradford, New York.

- 22Jameson, J. Franklin- 1909 Narratives of New Netherland, 1609-1664. Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York.

- 23Josephy, Alvin M., Jr.- 1982 Now That the Buffalo’s Gone: A Study of Today’s American Indians. Knopf, New York.

- 24Karlis Karklins- 1974 Seventeenth Century Dutch Beads. Historical Archaeology; 8:64-82.

- 25Kemp, Francis Adrian Van der (trans.)- 1841 A History of the New Netherlands, by Sir N.C. Lambrechtsen. Collections of the New-York Historical Society, 2nd series. New York.

- 26Laer, A.J.F. van (trans.)- 1924 Documents Relating to New Netherland, 1624-1626. The Henry E. Huntington Library and Art Gallery, San Marino, CA.

- 27Lamb, Martha J.- 1877 History of the City of New York. 3 vols. A.S. Barnes, New York.

- 28Macauley, James- 1829 The Natural, Statistical, and Civil History of the State of New-York. Gould & Banks, New York.

- 29Mather, Joseph H.- 1848 A Geographical History of the State of New York. Hawley Fuller, New York.

- 30“The Melyen Papers”- 1913 Collections of the New-York Historical Society 46. New York.

- 31Morison, Samuel Eliot (ed.)- 1963 Journals and Other Documents on the Life and Voyages of Christopher Columbus. Limited Editions Club, New York.

- 32Morison, Samuel Eliot- 1965 The Oxford History of the American People. Limited Editions Club, New York.

- 33Moulton, Joseph W.- 1826 Novum Belgium. Bliss & White, New York.

- 34O’Callaghan, E.B. (ed.)- 1856 Documents Relative to the Colonial History of the State of New York. 11 vols. Weed, Parsons, Albany.

- 35Van Pelt, Daniel- 1898 Leslie’s History of the Greater New York. Arkell, New York.

- 36Purchas, Samuel- 1626 Purchas His Pilgrimes. Reprinted in 1966, Glasgow.

- 37Randall, S.S.- 1870 History of the State of New York. J.B. Ford, New York.

- 38Raden, Aja- 2015 Keep the Change: The Beads that Bought Manhattan, Huffington Post Online

- 39Schuyler, George W.- 1885 Colonial New York. Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York.

- 40Schwartz, Melvin and John R. O’Connor- 1981 The New Exploring American History. Globe, New York.

- 41Sleen, W.G.N. van der- 1962 The Production of “Antique Beads” in Amsterdam in the Seventeenth Century.” Annales du 2eme Congres des Journées lnternationales du Verre, pp. 81-89.

- 42Smith, William, Jr.- 1757 History of the Province of New-York. T. Wilcox, London.

- 43Stone, William L.- 1872 History of New York City. Virtue & Yorston, New York.

- 44Sullivan, James- 1927 History of New York State, 1523-1927. Lewis Historical Publishing Co., New York.

- 45Tyrrell, William G.- 1963 We New Yorkers. Oxford Book Co., New York.

- 46Valentine, David T.- 1853 History of the City of New York. G.P. Putnam, New York.

- 47Vogelvanger- 1859 The Manhattan Papers. The Sunday Times. New York State 1860 Library, Albany.

- 48Watson, John F.- 1846 Annals and Occurrences of New York City and State, in the Olden Times. H.F. Anners, Philadelphia.

- 49Weslager, C.A.- 1968 Did Minuit Buy Manhattan Island from the Indians? De Halve Maen 43:6.

- 50Wilson, James G.- 1892 The Memorial History of the City of New York. New-York History, New York.

- 51Yates, John van Ness- 1824 History of the State of New-York, Vol. 1, Part 1. Ante- Colonial Annals. A.T. Goodrich, New York.

- 52Zabriskie, George Olin and Alice P. Kenney- 1977a The Founding of New Amsterdam: Fact and Fiction. Part IV, The Growth of a Myth. De Halve Maen 51; 1977b The Founding of New Amsterdam: Fact and Fiction. Part V, The Purchase of Manhattan. De Halve Maen 52.

Rendezvous & Historic Reenactment Articles

Rendezvous & Historic Reenactment Resources

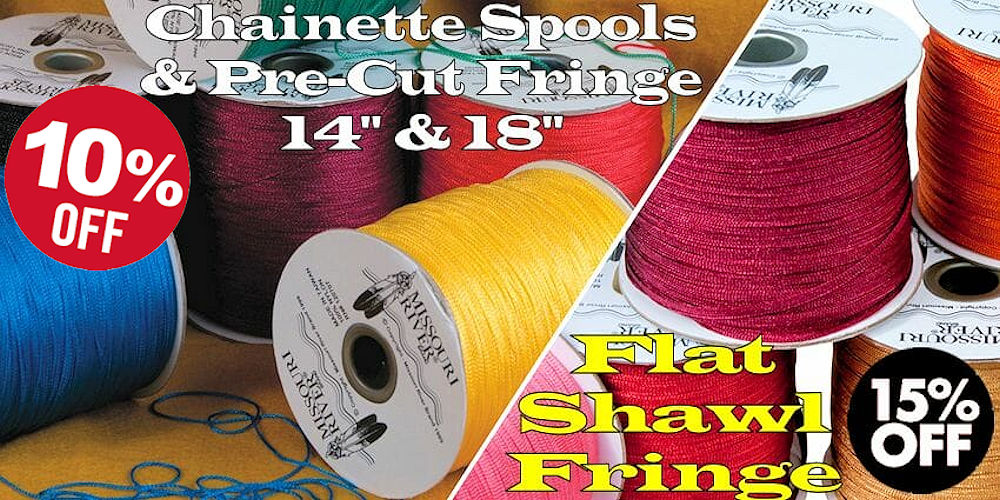

Current Crow Calls Sale

January – February

SAVE 10%-25% on popular powwow, rendezvous, historic reenactor, bead & leather crafter supplies. Crazy Crow is starting out the New Year with savings on many popular craft supply items like Plains Hard Sole Moccasin Kits, Chainette Spool and Pre-Cut 14 & 18 inch Fringe, Flat Spool Fringe, as well as big savings on very popular items like most types of our brass beads, artificial sinew, bone hair pipes, Peyote Kettles and Drum Covers, select hand-made Frontier Knives, and engraved brass sleigh bells. Of course you can order everything online 24×7.