History of Writing in Colonial America

Writing Materials & Learning to Write

Credit Above Photo: Watts Photos, All rights reserved by watts_photos

History of Writing

in Colonial America

Writing Materials & Learning to Write

By Crazy Crow Trading Post ~ July 3, 2023

Credit Above Photo: Watts Photos, All rights reserved by watts_photos

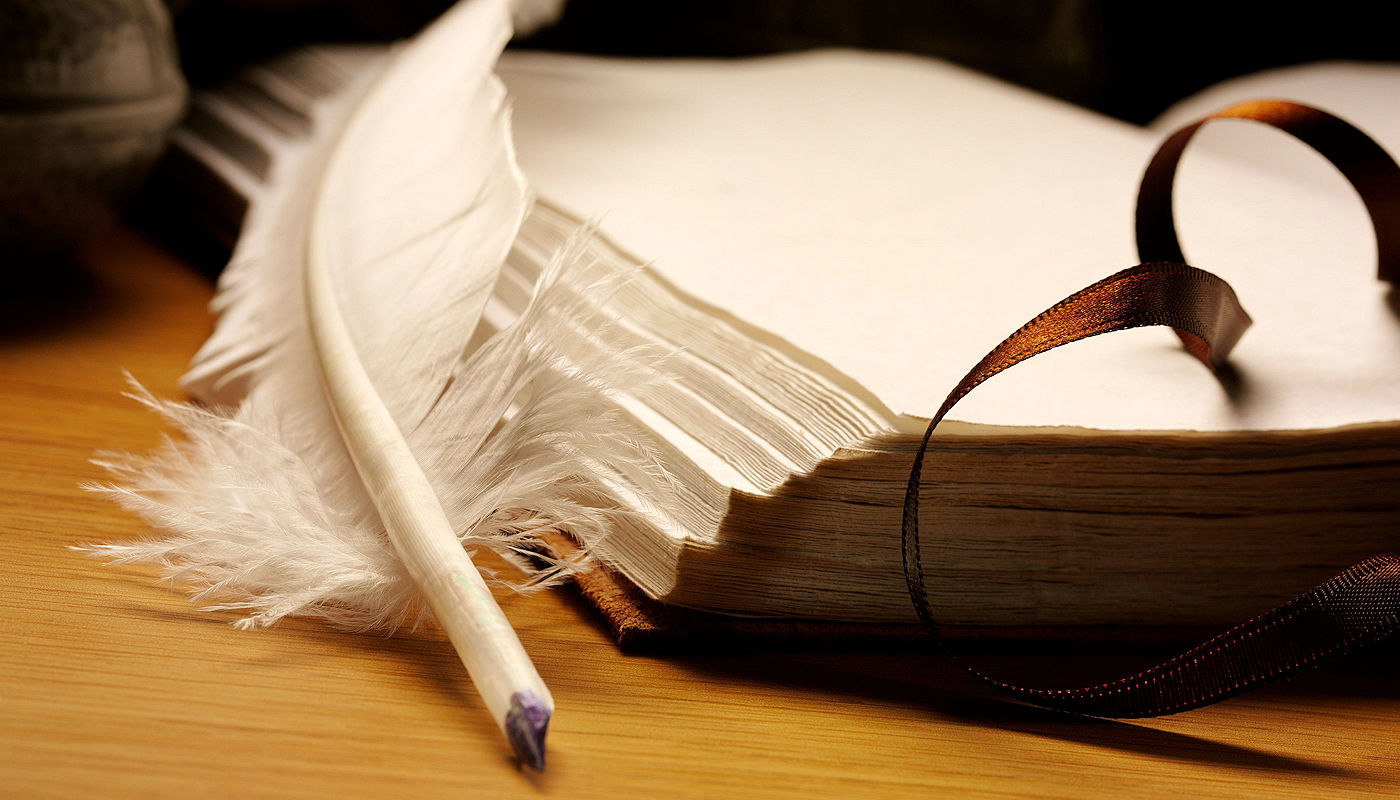

Writing in the Colonial America era, was a complex technical process that required an array of materials and techniques, many of which were often difficult or expensive to acquire. Some of the personal writing tools used in colonial America included quill pens, ink, journals, paper, stoneware inkwells, sealing wax (the idea of separate envelopes did not exist) and portable writing desks that could be placed on another table top or in the lap.[1] Formal writing instruction was deliberately limited to certain elite classes of the time of both sexes and men of business and trade.

Credit Above Photo: Canva

QUILL PENS date to the Dark Ages, when bird feathers replaced the hollow reeds the Romans used. Thomas Jefferson bred special geese to keep himself supplied. Because of their shape, only the five feathers at the tip of the left wing were used; left-handers could use feathers from the right wing—and it was best to pull them in the spring. The trick then was to bury the feathers in hot, dry sand to harden the points, after which it was time to get your penknife out: the better the cut, the finer the script. Britain imported twenty-seven million quills a year from Russia alone to meet the demand. For almost 1,500 years, people used quill pens to write letters. By the middle of the 19th century, however, steel nibs were well on their way to ousting the quill. [10]

18th Century Writing Supplies

Credit Above Photo: National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

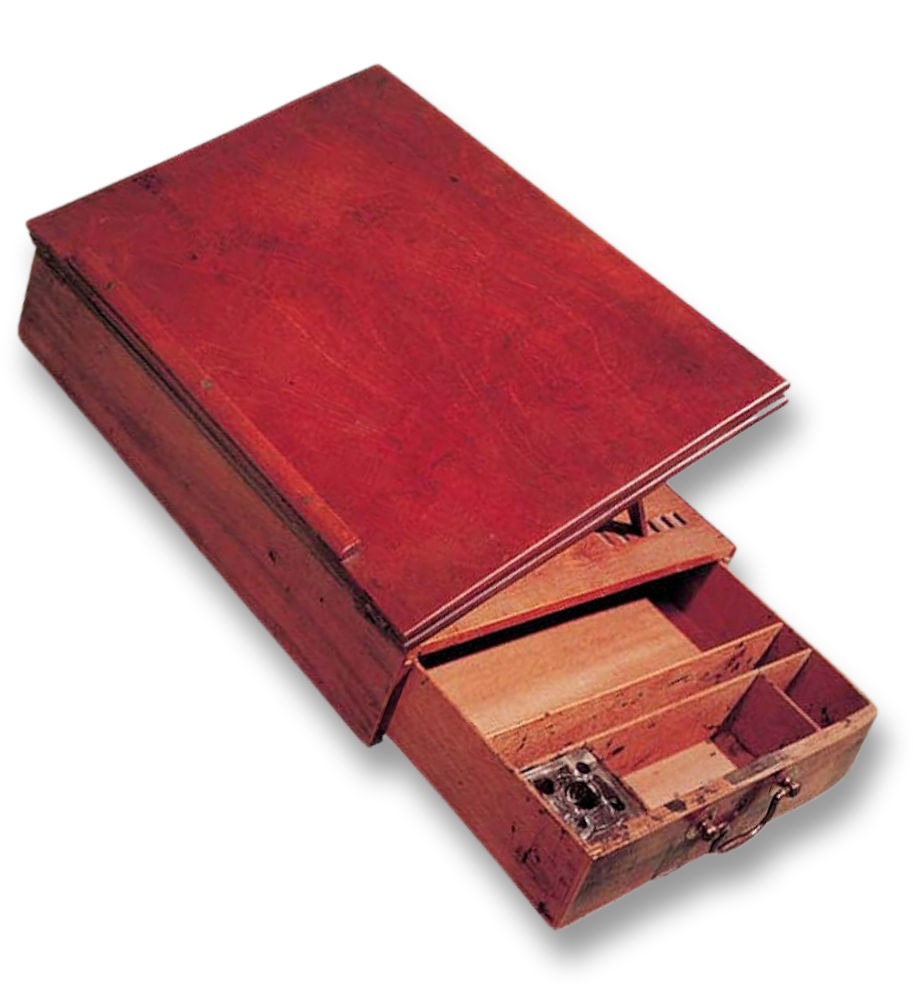

Thomas Jefferson’s Portable Desk

Thomas Jefferson’s portable desk, of his own design [2], features a hinged writing board and a locking drawer for papers, pens, and inkwell. This desk continued to be Jefferson’s companion throughout his life as a revolutionary patriot, American diplomat and president of the United States. While the drafts of the Declaration of Independence were among the first documents Jefferson wrote on this desk, the note he attached under the writing board in 1825 was among the last: “Politics as well as Religion has its superstitions. These, gaining strength with time, may, one day, give imaginary value to this relic, for its great association with the birth of the Great Charter of our Independence.” [3]

As the delegate from Virginia to the Continental Congress in 1776, Jefferson had the “writing box,” as he called it, built by a Philadelphia cabinetmaker named Benjamin Randolph. It’s made of mahogany and is about 10 inches long by 14 inches wide by 3 inches deep, but it does a lot with the limited space. The desk includes a folding board attached to the top to increase the writing surface, as well as a lockable drawer with space for paper, pens and a glass inkwell. [11]

On Nov. 14, 1825, Jefferson wrote to his recently married granddaughter Ellen Randolph Coolidge to inform her that he was sending his “writing box” as a present to her husband Joseph Coolidge. The desk remained in the Coolidge family until April 1880, when the family donated it to the U.S. government. It was transferred to the Smithsonian in 1921.[3]

How has the design of the portable writing desk change over time?

Of course the design of portable writing desks as well as the materials used in crafting them has changed over time. In the European tradition, the lap desk can be considered a modern form of the portable desk [4]. Antique lap desks were often strongly built of fine hardwoods like mahogany or walnut and had hinged writing surfaces, often covered in leather, felt, or other material, that flipped up to reveal storage space for papers. Individual compartments were designed to hold inkwells, pens, sealing wax, and other contemporary writing materials. Some desks also had concealed storage compartments [4]. Modern lap desks are meant primarily for use in bed and other similar circumstances and are much smaller and simpler than antique lap desks. They are also made of much cheaper materials [4].

Learning Reading & Writing in the 18th & 19th Centuries

Prior to the early twentieth century, reading and writing were taught to children at different ages as separate skills. Typically children learned to read around the ages of 4 to 7, while writing instruction was delayed till between ages 9 and 12. This delay allowed children to develop the manual dexterity to use a quill pen, and to focus on the oral-based reading instruction of the period. Another challenge that beginners faced was immediately learning to write in “cursive”, or script, since “print” handwriting, so-called because it mirrored printed type, was reserved for specialized uses like labeling parcels. [1]

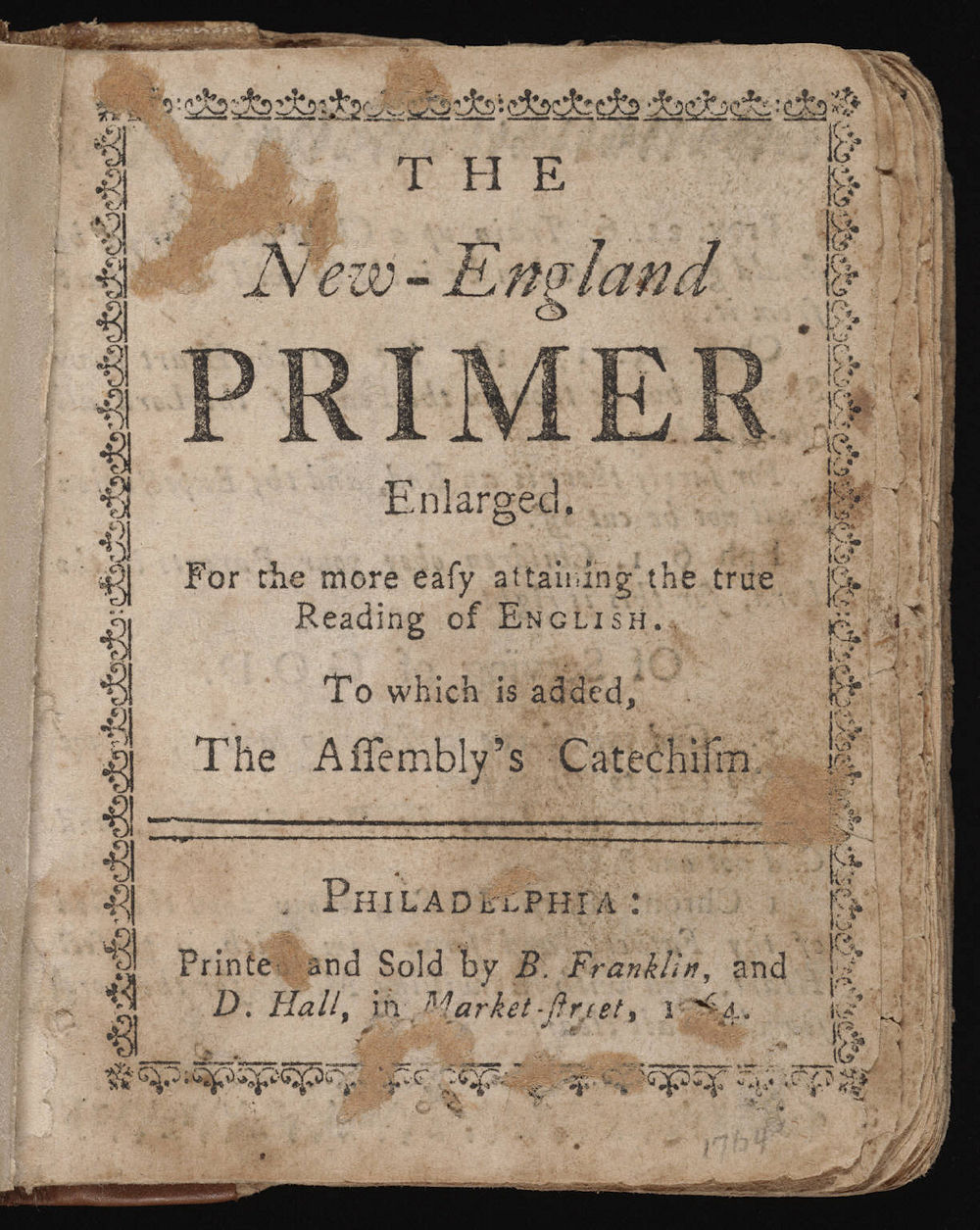

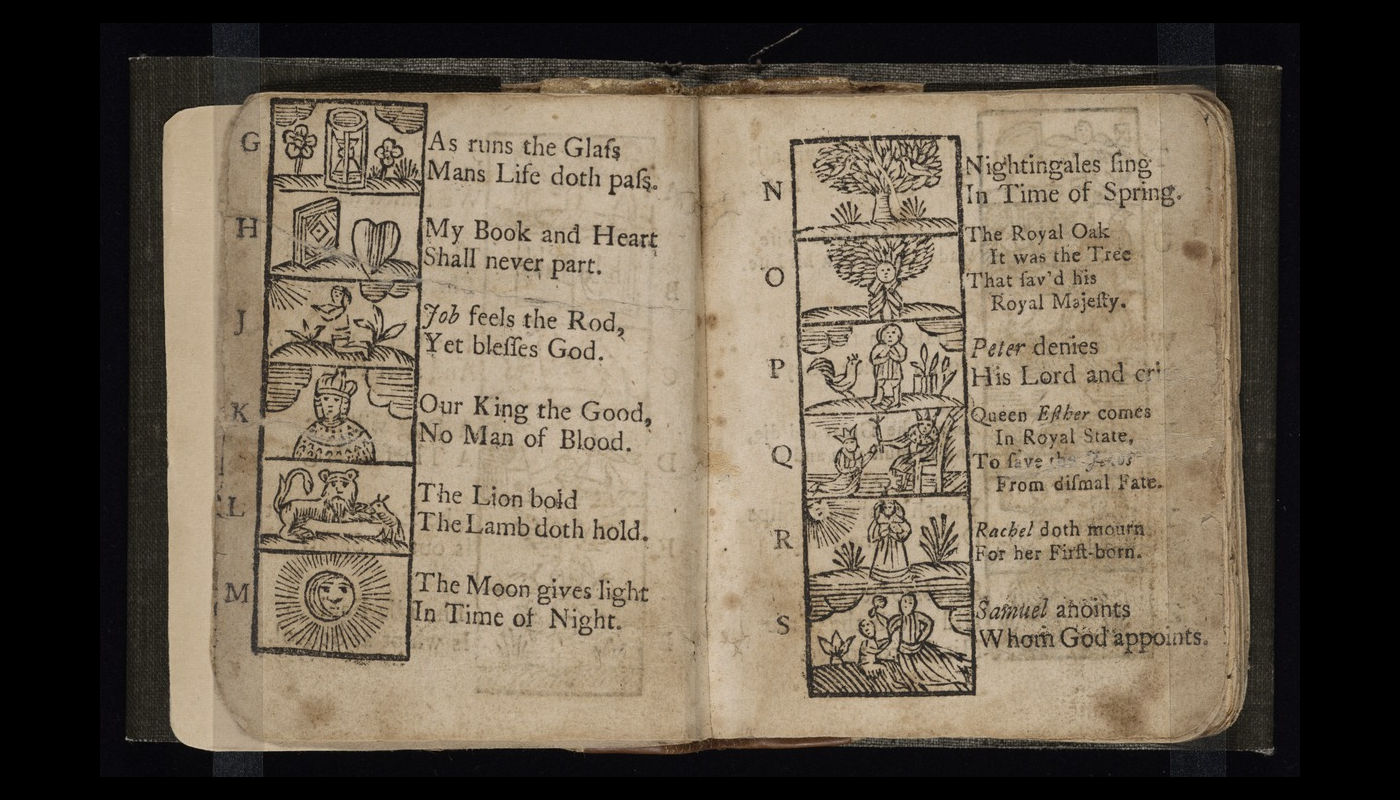

Credit Above Photo: 1764 edition, public domain, Conservapedia

The New England Primer was the first reading primer designed for the American colonies. It became the most successful educational textbook published in 17th-century colonial United States and it became the foundation of most schooling before the 1790s. In the 17th century, the schoolbooks in use had been Bibles brought over from England. By 1690, Boston publishers were reprinting the English Protestant Tutor under the title of The New England Primer. The Primer included additional material that made it widely popular with colonial schools until it was supplanted by Noah Webster’s Blue Back Speller after 1790.[12]

John Locke wrote in the late 17th century that the best way to get a child to write was “to get a plate graved with the characters of such a hand as you like best… let several sheets of good writing-paper be printed off with red ink, which he has nothing to do but go over with a good pen fill’d with black ink”, a pedagogical method that remained constant throughout the eighteenth century.1 From letters students moved on to copy increasingly complex sentences and letters. Advanced students sometimes combined their lessons in mathematics and languages into elaborate manuscripts, as George Washington did in an exercise book concerning geometry when he was 12. [6]

The division of literacy education into two distinct and sequentially separated skills meant that the inability to write did not necessarily imply an inability to read. While basic reading ability in America in the eighteenth century was widely considered to be a spiritual necessity regardless of a person’s class, gender, or race, writing instruction was deliberately limited to elite whites of both sexes and men of business and trade.

Good penmanship was an essential skill for merchants. “Writing is the First Step, and Essential in furnishing out the Man of Business,” wrote the English teacher and author Thomas Watts in 1716, and business manuals throughout the eighteenth century tied good handwriting directly to a merchant’s reputation and credit. [7]

These manuals made it clear that business handwriting should be easy to read and quick to write. They advised those destined for the clerk’s desk or the merchant’s counting house to adopt a bold and neat hand (an 18th century term for script) such as the round hand, or the quick running hand. The latter could be written more quickly because its letters were sloped and connected to one another.

Developing proper handwriting was an essential part of the social education of the 18th-century gentleman as well. In contrast to merchants, writing manuals suggested young gentlemen practice until their handwriting looked effortless, easy, and disengaged. To achieve this end, penmanship books often recommended a variant on the running hand that would mark the genteel writer as distinct from the mercantile scrivener. Thomas Jefferson commented that George Washington “wrote readily, rather diffusely, in an easy correct style.” [8]

Among women, writing was a skill largely restricted to elite gentry in the early 18th century. Female literacy increased over the course of the 18th century as it became a necessary polite refinement for the upwardly mobile as well as household management.

Girls often learned in private settings from relatives or tutors, or in private female academies, where writing was taught as an accomplishment alongside skills like needlework and musical ability. Ideally their round or running hand would reflect the writer’s feminine sensibilities.

In areas of colonial America with public schools, such as Massachusetts, boys destined for business often learned in publically-funded writing schools. Children in the German-speaking areas of Pennsylvania often learned to write in mixed-gender church and fee-funded schools, and children and adults of both sexes learned to write from private tutors or at home throughout the colonies.

The forms for handwriting were conveyed through penmanship books, which were usually illustrated with costly copperplate engravings and almost exclusively imported into America before the 1790s. Many penmanship manuals also contained introductions to grammar, arithmetic, and accounting.

The categorization of different scripts by class and gender was reflected in the copy-phrases used in penmanship manuals: phrases for women and elite men often used moral maxims, while copy-books aimed at aspiring clerks contained bills and arithmetic problems.

Letter writing manuals grew in popularity as correspondence became a fashionable hobby for the upwardly-mobile in the mid-eighteenth century. These books advised correspondents on the various conventions of writing a letter, as well as the correct ways to address and seal it.

Resources

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5Locke, John. Some Thoughts Concerning Education. London, 1693. Reprint, Pitt Press, Cambridge, 1898, 136.

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

Select 18th-19th Century Historic Reenactor, Rendezvous, Shooter & Camp Products from Crazy Crow

Whatever your historic reenactor needs (other than guns), Crazy Crow Trading Post has it! As the largest supplier of Native American Indian crafts and craft supplies (which are what rendezvous-lovers use as well) we have everything for all types of mountain man clothes and gear. From head to foot, we can outfit you (or help you make your own) to get you ready for your first (or fifty-first) mountain man rendezvous or black powder shooting event. We also supply French & Indian War, American Revolutionary War, War of 1812, and American Civil War reenactors as well.

18th & 19th Century American Historic Reenactor & Rendezvous Camp Central: We’re also your historic reenactor, rendezvous & primitive camping supply center too. From cast iron firetools and cookware to wedge tents and a great selection of personal gear, we’ll have everything to make your stay at the French & Indian War, Revolutionary War, War of 1812, rendezvous, buckskinner, voyageur, Civil War or just your own primitive camping more authentic and enjoyable.

Rendezvous & Historic Reenactment Articles

Rendezvous & Historic Reenactment Resources

Current Crow Calls Sale

January – February

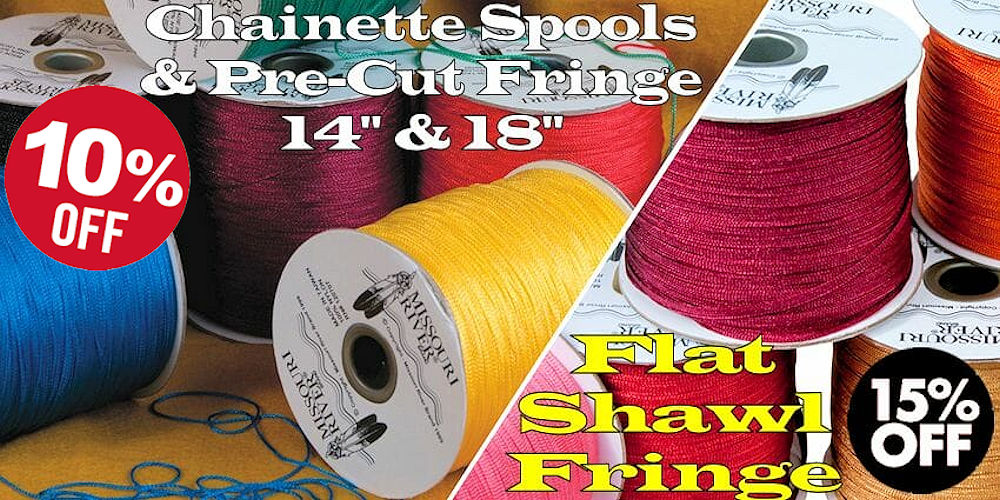

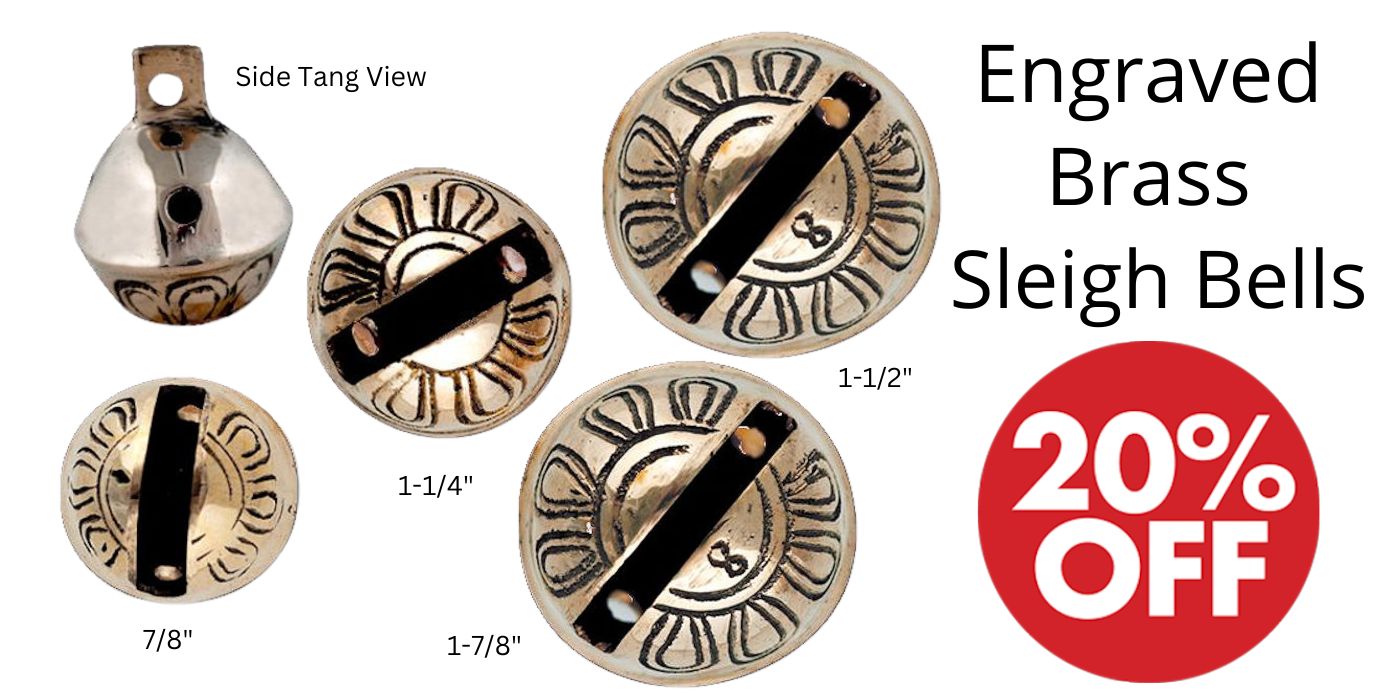

SAVE 10%-25% on popular powwow, rendezvous, historic reenactor, bead & leather crafter supplies. Crazy Crow is starting out the New Year with savings on many popular craft supply items like Plains Hard Sole Moccasin Kits, Chainette Spool and Pre-Cut 14 & 18 inch Fringe, Flat Spool Fringe, as well as big savings on very popular items like most types of our brass beads, artificial sinew, bone hair pipes, Peyote Kettles and Drum Covers, select hand-made Frontier Knives, and engraved brass sleigh bells. Of course you can order everything online 24×7.